Ondrej Markus

Entrepreneur in ed-tech, building the future of education as a founder and CEO at Playful.

I write about the future of education, designing learning games, and running a startup.

I'm a generalist, introvert, gamer, and optimizing to be useful.

The 85 % rule: Be the best by trying less

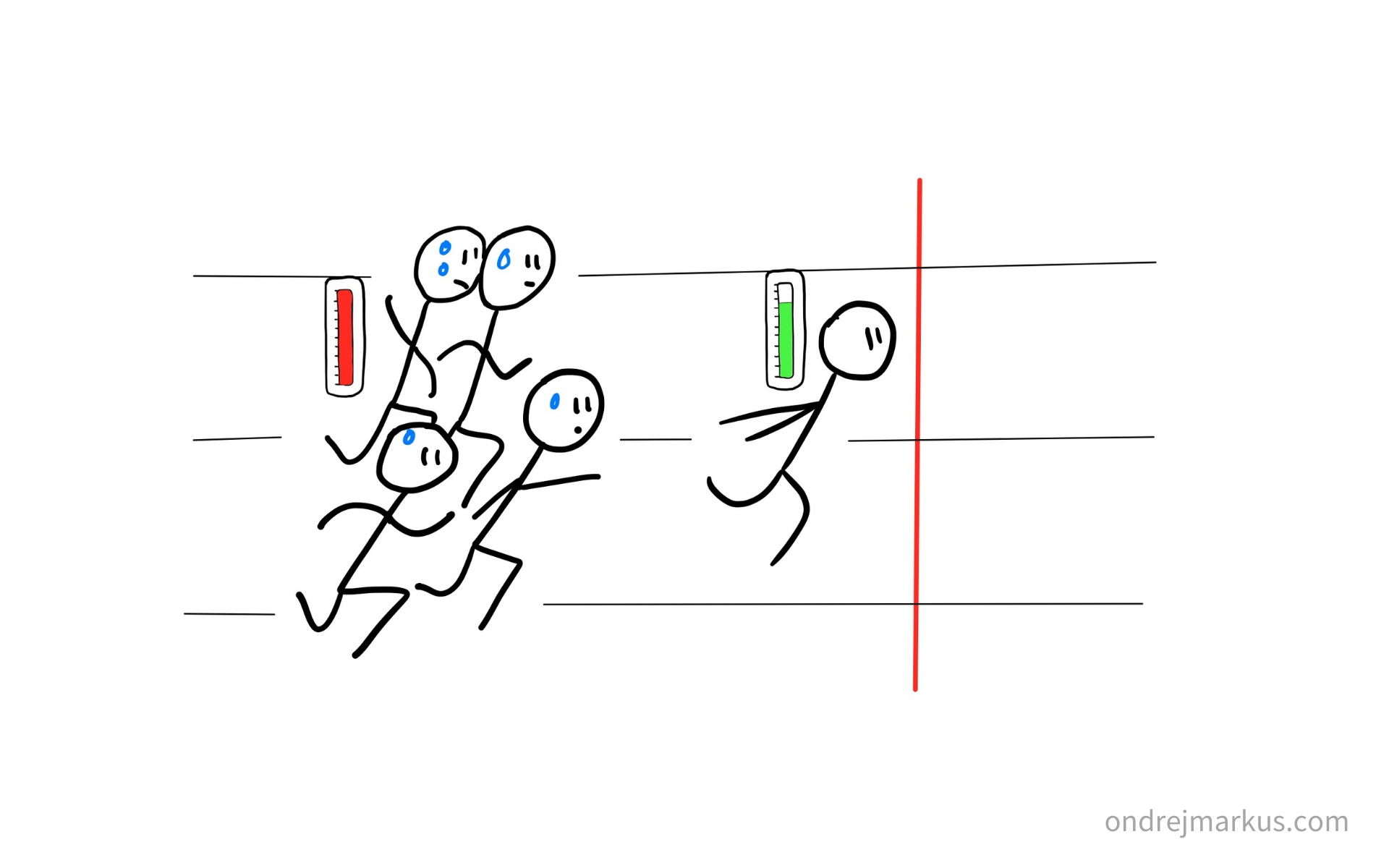

The best sprinter of the last century, Carl Lewis, won most of his 100-meter races in a curious way. He was usually in the last place the first 50 meters but swept past his opponents in the second half of the race. (1)

This unusual thing impressed one coach so much he studied dozens of videotapes to understand what is going on. After weeks of research, he found a fascinating difference between Lewis and the other runners.

It was his opponents who changed in the second half of the race. As they approached the finish line, they started trying too hard, and with their fists clenched and muscles strained, they began to slow down more quickly.

In the meantime, Lewis stayed relaxed from start to finish, maintained his speed, and beat them because of it.

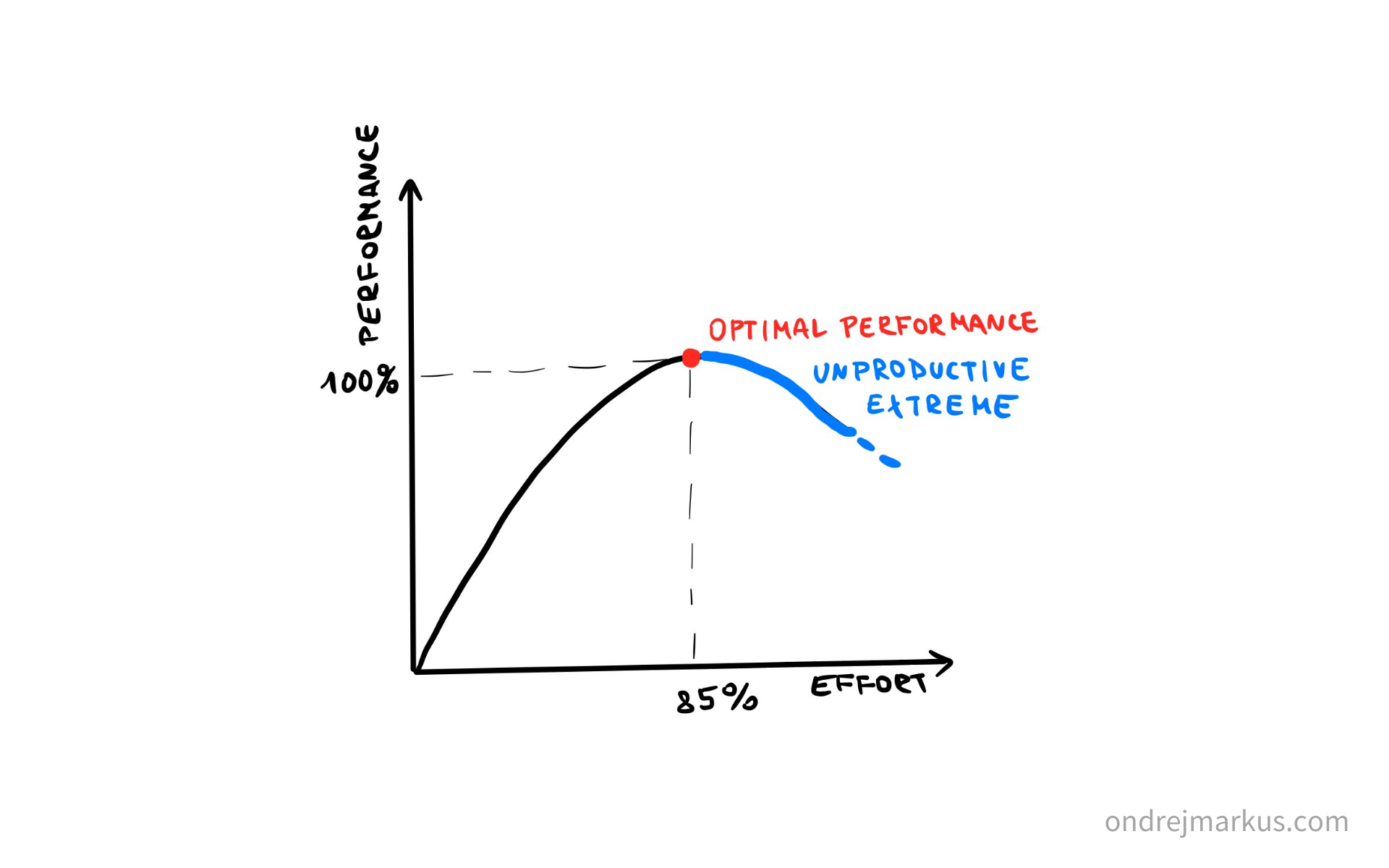

The 85 % rule was born as a catchy-sounding reminder that pushing yourself too much can hurt your performance.

Work smarter, not harder

Whether you are an athlete, entrepreneur, artist, writer, student, or anyone who cares about their results, you probably want to do your best.

But the first thing you need to understand is that doing the best you can is different than pushing yourself to the extreme.

The smart thing to do is to know your limits and play around them. The stupid thing to do is recklessly forcing yourself to try harder at any cost. There is a ceiling above which extra effort becomes counter-productive.

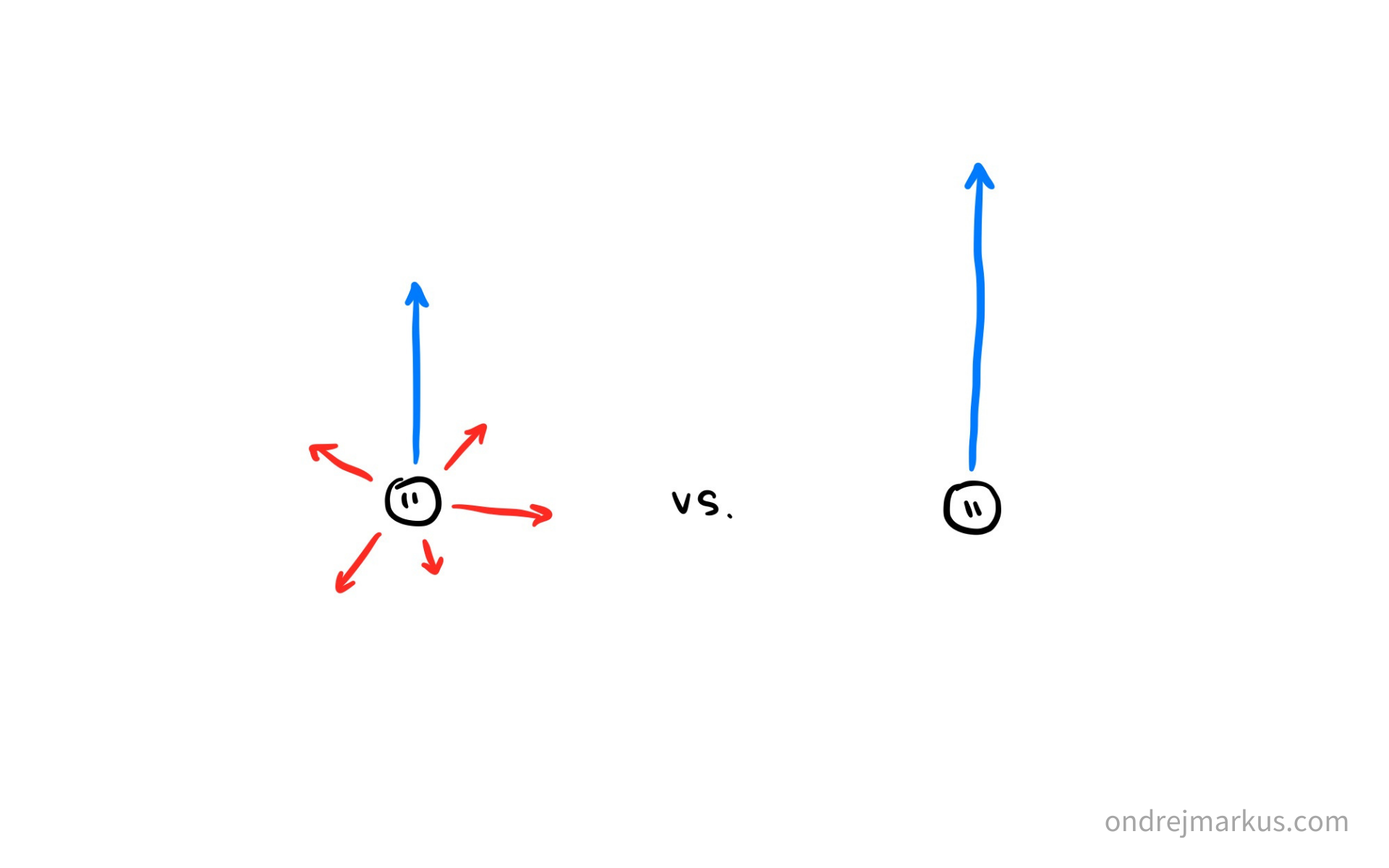

Optimum vs. Extreme

That’s what the 85 % rule is standing for. It doesn’t say you can half-ass your way through life and expect remarkable results. That’s unlikely. You still have to strive for the best possible results with everything you have. The difference is that you rely on self-control instead of brute force.

Wherever you look in everyday life, you can see evidence that trying too hard doesn’t work. We intuitively know this, yet for some reason, we keep forgetting it.

- When you try too much to impress someone to like you, chances are they won’t.

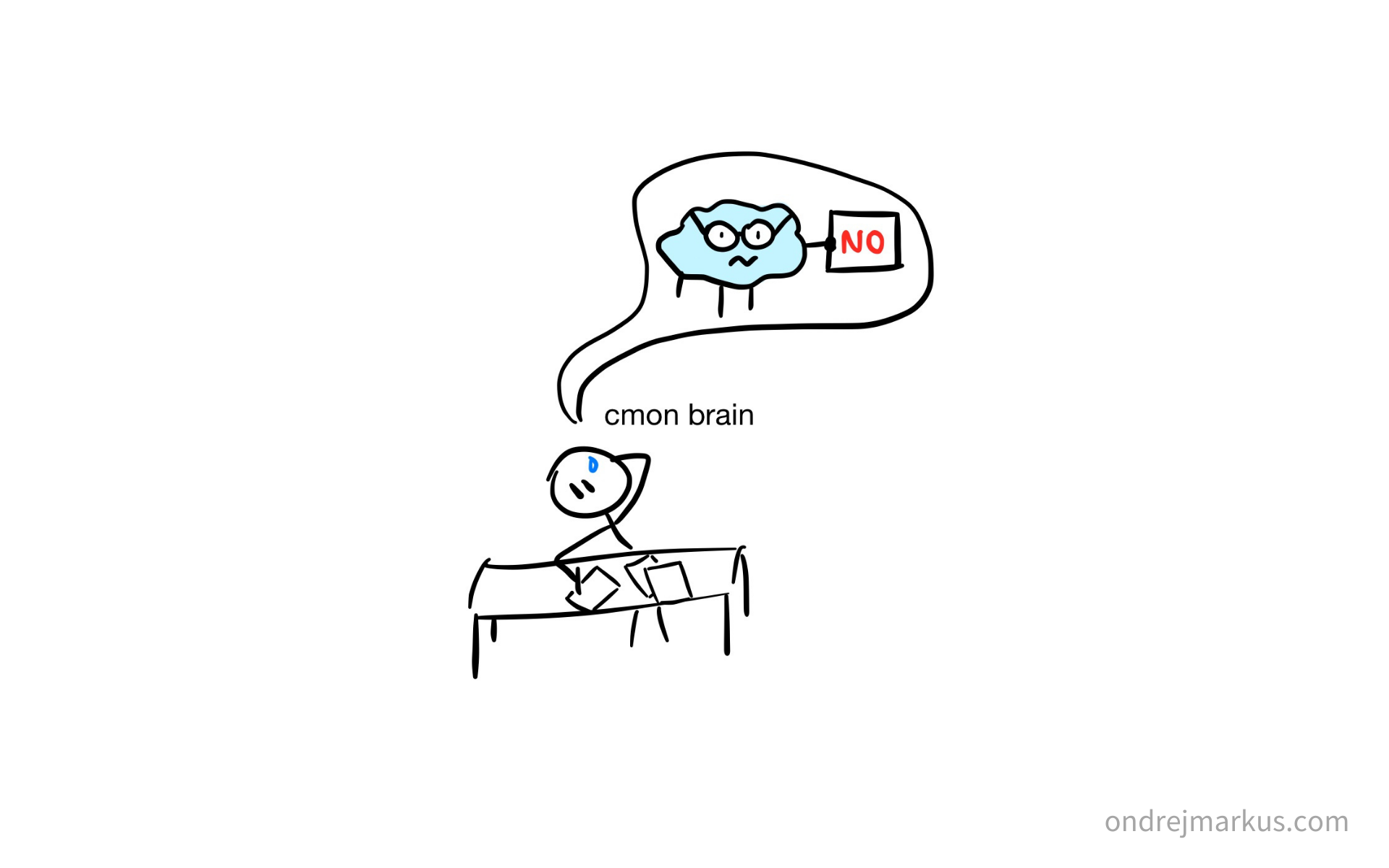

- When you try to fall asleep too rigorously, it takes longer.

- When you try to spark a genius idea on command, your brain goes blank.

When brain goes on a strike

Learn to control your attention

Your mind can be its worst enemy if it’s free to do whatever it wants. Attention is the name of the game when it comes to optimal performance. It directs where your energy goes. And if it doesn’t go where you need it most, expect trouble.

During a performance, you need all your attention solely on the activity. When it’s fully there, your mind stops wandering, and it almost feels like nothing else exists beyond what you are doing. There is no anxiety, no pressure, no nagging voice telling you to push harder. You are relaxed yet focused.

But when your attention slips away, you begin to over-analyze what is going on. Attention shifts from the activity to yourself, and you become too self-conscious. Your mind starts to comment on how badly you’re doing instead of focusing on the task.

You can’t be aware of performing and have all attention on the activity at the same time. These two things are mutually exclusive. That means you either are in optimal performance, or you think about it, never both.

The counter-intuitive part of getting into your optimum is that you need to relax and try less, not more. It’s trying too much that’s blocking you from maintaining optimal performance.

The real battle isn’t happening on the field, stage, or screen, but in your head.

Get better at trying less

There are two things I do daily to overcome the unproductive self-talk that’s often the difference between a good day and a bad day.

Bad day of writing

Good day of writing

1. Practice quantity

The more you do something, the less you have to think about it.

For example, as I write more, some mechanical skills like typing, vocabulary, and grammar get more automatic with repetition. That means fewer things for me to get self-conscious about and more attention flowing where it’s productive.

That’s why beginnings can be extra hard. You start a new project and start finding out how much you don’t know and how bad you are in comparison to the titans of the field. At that point, the best thing to do is to commit to practice quantity and know that it gets better.

2. Take things less seriously

It’s impossible to relax when you put too much pressure on yourself. Whether it’s self-imposed expectations or you’re nervous before an audience, it adds up to stress that makes you self-conscious.

One antidote I use is to follow the fun and take things a little less seriously. When I get too tense and stop having fun, things don’t work. I often catch myself with strained shoulders and shallow breathing during work. Chill man, you’re reading a book, not performing brain surgery.

Everyone has to experiment with what works for them, but I suspect most high-achievers need to relax a bit rather than push harder.

Footnotes

- (1): Hugh Jackman mentioned this story on the episode #444 of Tim Ferriss Show.