Ondrej Markus

Entrepreneur in ed-tech, building the future of education as a founder and CEO at Playful.

I write about the future of education, designing learning games, and running a startup.

I'm a generalist, introvert, gamer, and optimizing to be useful.

Creative routine: How to do your best work as a creator

I’m fascinated by how different people with different personalities get their creative work done.

That’s why I read the book Daily Rituals – How Artists Work by Mason Currey. It’s a catalog of 161 writers, painters, architects, filmmakers, and others who have spent their lives making a living as professional creators.

The book asks good questions:

- How to do meaningful creative work while also earning a living?

- How to make the time each day to do your best work?

- How to organize your schedule to be creative and productive?

Today, I want to share with you some of my favorite snippets and insights from the book to help you find a creative routine that works for you.

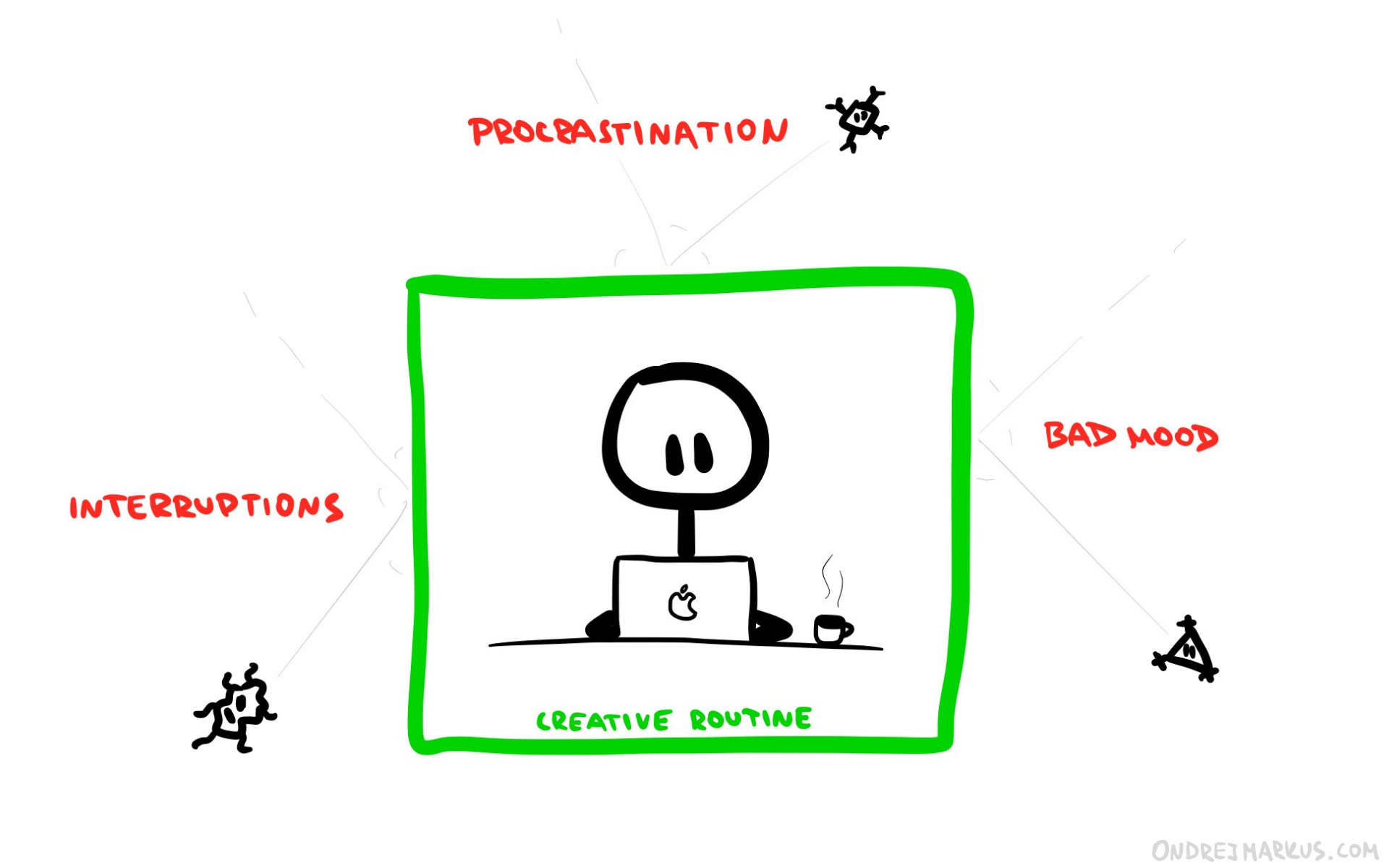

Routine is your sanity fortress

A solid routine fosters a well-worn groove for one’s mental energies and helps stave off the tyranny of moods. – Daily Rituals

Creative routine is a sanity fortress.

Let’s start by defining routine:

Routine is a sequence of actions you repeat every day to do your best work.

Its purpose is to help you make good use of the limited resources you have: time, energy, and attention. And to help you do it even on a bad day.

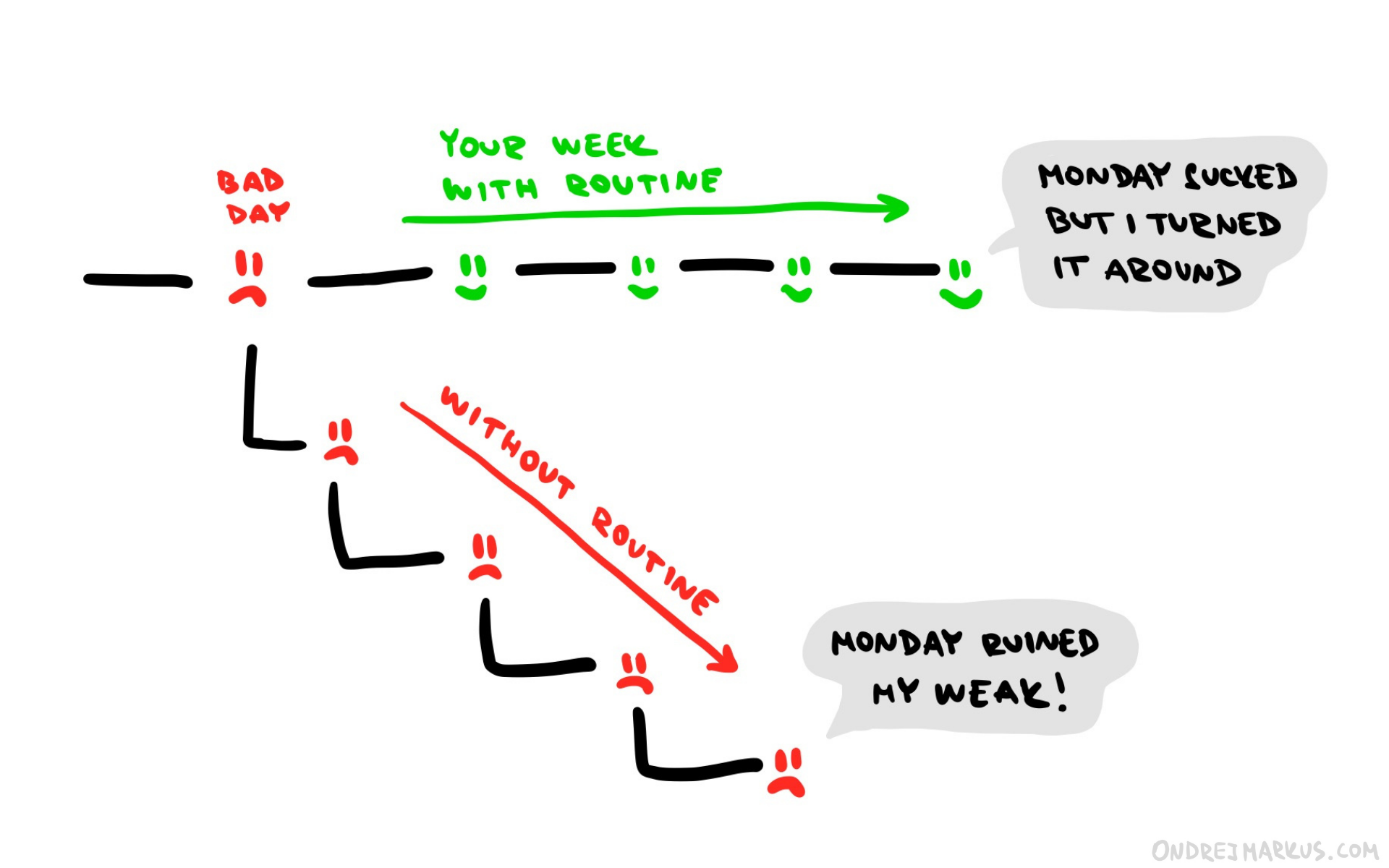

I have at least one bad day a week when I don’t feel like doing the work. Sure, skipping one day would be okay. But the problem is, if you’re not careful, a bad day can spiral into a bad week, which can become a bad month, etc.

A good routine prevents bad days from cascading into bad weeks.

A good routine prevents bad days from cascading into bad weeks.

A bad day plus a solid routine ends up being a slightly below-average day you can work with and not get stuck.

But is it necessary or even smart to work when you have a bad day?

Not everyone agrees on that.

To structure or not to structure

Some successful authors wrote just when they felt the urge to write, and it worked for them.

So even if the word ‘discipline’ gives you goosebumps, making a living as a creative seems doable.

I really don’t adhere to schedules at all, and don’t have the slightest desire to do that. The times that I’ve tried that, when I have been in a slump and I try to get out of it by saying, ‘Come on, Ann, sit down at that typewriter,’ I’ve gotten in a worse slump. It’s better if I just let it ride… I’ve learned I can’t force it.” – Ann Beattie (b. 1947)

“I really am incapable of discipline. I write when something makes a strong claim on me. When I don’t feel like writing, I absolutely don’t feel like writing. I tried that work ethic thing a couple of times … but if there’s not something on my mind that I really want to write about, I tend to write something that I hate. And that depresses me. Maybe it’s a question of discipline, maybe temperament, who knows?” – Marilynne Robinson (b. 1943)

However, most creators, especially writers, seem to thrive on systems and repetition.

When he is writing a novel, Murakami wakes at 4:00 A.M. and works for five to six hours straight. In the afternoons he runs or swims, does errands, reads, and listens to music. Bedtime is 9:00.

“I keep to this routine every day without variation. The repetition itself becomes the important thing. It’s a form of mesmerism. I mesmerize myself to reach a deeper state of mind.” – Haruki Murakami (b. 1949)

I live in the repetition camp. I need structure.

I write every morning except Saturdays. I work offline without interruptions of email or notifications. And I have a strict ‘No meetings before noon’ policy because mornings are my natural energy peek of the day I want to spend on my most important work – writing.

No meetings before noon.

My routine is simple:

- I wake up without an alarm. (Ideally, I went to bed at a reasonable time.)

- I make coffee. (I grind the beans manually as my brain slowly boots up its higher functions.)

- I journal in my Morning Pages to clean the windshield of my mind.

- And then I write until about noon when I eat breakfast, which ends the routine.

That’s it.

My afternoons are much more messy and unpredictable, but it doesn’t matter. If I did my work in the morning, I won the day already.

Work more to get ____ done

Another interesting difference between creatives is how much they work.

Some embrace the hustle and work as much as possible:

“I write and write and write… As a result I have aquired the reputation of being prolific when in fact I am measured against people who simply don’t work as hard or as long.” – Joyce Carol Oates (b. 1938)

Others, me included, are happy with 2-3 hours of really good deep work per day. And anything beyond that feels like a bonus.

“Everyone assumes I’m a systematic and nose-to-the-grind kind of person, but to me it seems like a part-time job, really, in that writing from 11 to 1 continuously is a very good day’s work. Then you can read or play tennis. Two hours. I think most writers would be very happy with two hours of concentrated work.” – Martin Amis (b. 1949)

When in doubt, go for a walk

But if creators have one thing in common, it’s that they do a lot of walking.

After a midday dinner, Beethoven embarked on a long, vigorous walk, which would occupy much of the rest of the afternoon. He always carried a pencil and a couple of sheets of music paper in his pocket, to record chance musical thoughts. – Ludwig van Beethoven (1770–1827)

The Danish philosopher’s day was dominated by two pursuits: writing and walking. Typically, he wrote in the morning, set off on a long walk through Copenhagen at noon, and then returned to his writing for the rest of the day and into the evening. The walks were where he had his best ideas, and sometimes he would be in such a hurry to get them down that, returning home, he would write standing up before his desk, still wearing his hat and gripping his walking stick or umbrella. – Søren Kierkegaard (1813-1855)

Ideas seem to flow more freely when you’re in motion. So go on more walks without headphones in your ears and just let your mind wander. Boredom stirs imagination.

Whatever works, works

Some of us adopt weird habits to keep our creative juice flowing.

“I’ve found over the years that any momentary change stimulates a fresh burst of mental energy. So if I’m in this room and then I go into the other room, it helps me. If I go outside to the street, it’s a huge help. If I go and take a shower it’s a big help. So I sometimes take extra showers. I’ll stand there with steaming hot water coming down for thirty or forty minutes, just thinking out ideas and working on plot.” – Woody Allen (b. 1935)

I’m among the weirdos.

I need to rearrange the furniture in my studio every 2-3 months. Otherwise, I get uninspired and bored in my room.

Me rearranging furniture to reset my creativity.

That applies to my digital environment too. For example, I change my writing app every few months.

I think this works for me because changing environments reset my perspective. I notice again things I started to ignore because they faded into the background.

The point is: Whatever works for you, do it. However weird it might seem to others.

The German poet, historian, philosopher, and playwright kept a drawer full of rotting appler in his workroom. He said that he needed their decaying smell in order to feel the urge to write. – Friedrich Schiller (1759–1805)

One of my pocket tactics to overcome particularly lazy days is going to a coffee shop.

Once I get there, I buy coffee and get to work. But, of course, I will not waste time watching Youtube now. I paid money to be there!

So, basically, I pay others money to make myself work.

So stupid. But so effective.

I pay others to make myself work.

The central insight from the book is that different people need wildly different routines to perform their best. Big surprise, I know.

But it’s an important reminder that chasing the newest routine of a creator you admire can be a waste of time because you simply have different needs and personality.

Recognize that you are weirdly unique, and figuring out what works for you is a puzzle nobody but you can solve.

So whatever ends up being your routine, if it works, it works. Nothing else matters. There is no single objectively correct routine for everyone’s creative work.

Look for inspiration in others, try new things, but keep only what helps you finish important work while enjoying the process.