Ondrej Markus

Entrepreneur in ed-tech, building the future of education as a founder and CEO at Playful.

I write about the future of education, designing learning games, and running a startup.

I'm a generalist, introvert, gamer, and optimizing to be useful.

Get from idea to paying customers in 4 weeks

This article is a case study of how I launched a course from idea to paying customers in four weeks.

I show exactly what I did so you can use it to create your own products with less time and effort.

Let’s go.

Part 1: So many ideas, so little time

In February 2021, I had an idea for a course.

I didn’t even know what exactly the course would be, only that it would be for creators and entrepreneurs.

Why did I want to do this?

- Peers: I craved a group of peer writers and entrepreneurs who work on various projects.

- Learning: I was looking to attend a similar course, but they are expensive as f****ck. I had the skills, tools, and know-how, so why not make my own, right?

- Enjoyment/business: I wanted to test facilitating a live online course to see if I enjoyed it enough to build a living around it. And, at the same time, see if there was a demand among creators/entrepreneurs for it.

My biggest constraint was time. I was busy working as a lead designer on a client project, running an entrepreneurship seminar at a university, and writing articles on this site.

I just couldn’t work on another project. So, to remove the time constraint, I approached it as a challenging experiment:

How would I do this if I had only an hour a week to make it?

This question changed everything.

Week 1: Checking stickiness

It’s important to emphasize that I started this as a low commitment experiment. I didn’t know if I will make the course happen or drop the idea in the process.

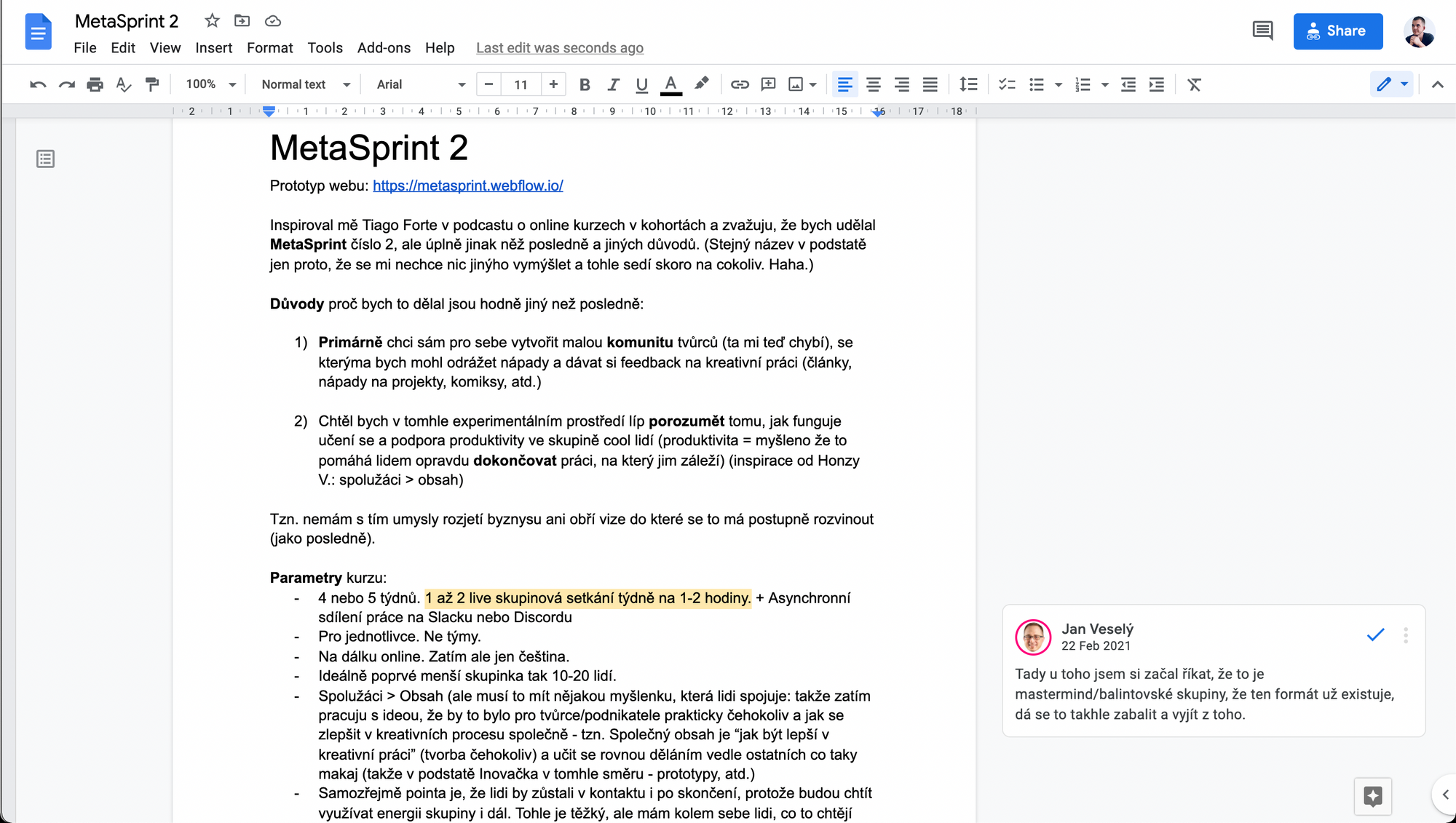

The first thing I did was dump all I knew about my idea into a Google Doc, and I sent it to a friend. (CZ)

Google Doc as a dumping place

I also made a poster prototype, which I like to make early in my design process because it helps me think visually and forces me to get specific.

Poster prototype helps me get more specific

Many of my ideas don’t survive this stage. I write them down, share them with a friend, and that’s it. They weren’t sticky enough. I just needed to get them out of my head.

Week 2: Rapid prototyping

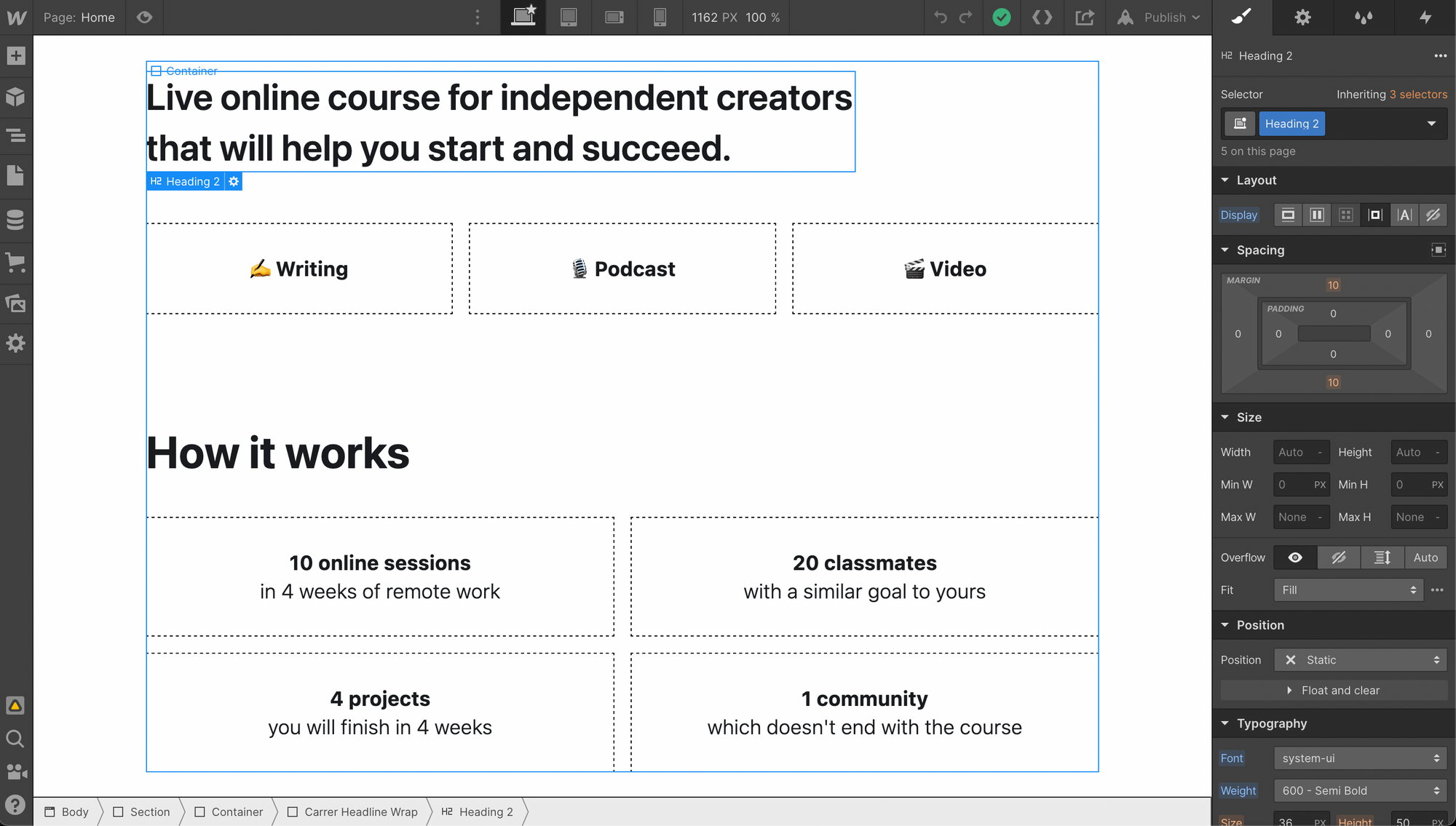

But this idea was not letting go of me. I kept thinking about it. So I took another hour to create a super simple website on Webflow (affiliate link) which I like to use for this exact use-case: making website prototypes.

You can quickly create a website there and host it on their domain for free. That’s good enough for a prototype.

My website was plain. Black and white, text-only. As I said, I had only about an hour to create it.

Editing the website prototype in Webflow

Important: I made the original prototype before I even knew who the course is for and how it should work. Its purpose was to have something specific to show people who I thought might be interested.

That same evening, I had a Zoom call with two friends who roughly matched my target group, so I took 5 minutes during our talk to show them the website and get first impressions.

I just asked them to think out loud as they scrolled down the website.

The result was: Confusion.

Insight: I realized that mixing creators and entrepreneurs is probably too much of a mess. It makes it unclear who the course is for and how it would work. So I decided to focus “only” on creators (writing, audio, video). I got more specific about who the customer is.

Week 3: Testing by asking for money

I improved the website prototype and moved on to more testing.

(Until now, I spent only 3-4 hours over three weeks on this project, and I still didn’t know if I was going to do it.)

I started testing by writing an email to three friends I knew might be interested in the course (all were writers or wanted to write more). It was a little different for everyone but the core was this:

Asking for feedback by email

In a day or two, they replied with feedback.

I continued improving the website as I realized who the course is for and how it should work. And I repeated the process with three other friends who fit my early adopters, but this time I added a price tag: $50.

Asking for feedback with an invitation and a price tag

(I set the price low because the goal wasn’t to profit at this point but to test the concept and create a group of peers. Profit was an objective for potential future runs.)

At this point, I started getting responses like: “I understand everything. I want in."

Insight: I decided to run the course if I get at least five people to enroll.

Week 4: Peer-to-peer selling

I finished the website, being as specific as I could with WHAT the course is, WHY it is useful, WHO it is for, HOW it works, and WHEN it will happen. It was still just a text-only website, but it worked fine. (The final prototype is still online here.)

I messaged another eight people I knew well enough to suspect this course was relevant to them.

Long story short, I asked 14 people, and seven said yes.

That’s it. Now, I knew I would run the course with seven people who wanted to start writing or write more. (There were no audio or video creators, which I later realized was for the best.)

Part 2: Lessons learned

Now, let’s highlight what I learned from this experience.

I won’t go through the operations of running the course here. I’ll just say that the course started two weeks after those seven people said yes. And, based on my impressions and talking to people afterward, it went well.

These are the main takeaways for me that you can use in building your next project:

Work less to move faster

My time constraint turned out to be fantastic for the design process. It streamlined my thinking to the essentials. No overthinking or struggle with perfectionism. I knew I only have an hour or two a week to work on this, so I focused on what mattered.

This doesn’t mean it’s always best to work as little as possible. But I definitely tend to get in my own way on projects as I spend more and more time on them (overthinking).

This case study is an argument for working on many projects simultaneously and sprinting fast on all of them.

Make rapid prototypes

Use that little time you have for a new project to create prototypes. It doesn’t matter that you don’t know what the thing will be yet. Making prototypes will help figure it out.

It’s the same as writing: You don’t always write after knowing what you want to say. You write to figure out what you want to say.

Create simple tweet prototypes, poster prototypes, website prototypes – whatever fits your project and plays into your strengths. Are you a visual person? Make posters and websites. Are you a words person? Write an article.

Show it to people early

Don’t work in secret. Unless you show your prototypes to people, you will not know how your product should work. Successful products exist on the overlap of your vision and what people want.

You can use the principles of building in public. Start by messaging your friends who fit the type of person you’re creating this for. If none of them does, find communities of people around the topic and share it there.

Sell it before you build it

Ideally, you want to be sure people will buy your product before you put hundreds of hours into it.

You want to sell people the idea before you create the product. Then once you have enough customers, you can go all-in on building it.

This might sound to you like scamming people, but it’s not. The rules for playing fair are simple: Never sell something you cannot deliver.

Build it as you go

It’s next to impossible to completely design a product in advance on a piece of paper because you don’t know what people will struggle with. So, ideally, you design things just-in-time based on what people really need.

You build the product as people use it and solve real problems on the go. You waste no effort on imagined issues and superficial needs.

For example, I prepared Monday’s sessions on Monday morning. A little stressful, but I could react to the exact problems and questions people encountered over the last week.

Epilog:

I enjoyed the course. I learned a lot, made some money ($350), and strengthened a couple of friendships. But, in the end, I decided not to do a second run.

I realized that organizing and facilitating a live course drains a lot of my energy which I decided to spend on writing instead.

However, figuring this out makes the experiment a success. I wouldn’t know this if I didn’t try it.

That’s the point of testing something with minimum effort. You don’t want to find out you don’t want to do something after spending six months on preparations. (I did that more than once, so I would know. Hehe.)

You don’t need a lot of time and resources to act on your ideas. You can start right now with what you have.

Move fast, make prototypes, and test by selling before you build the product.