Ondrej Markus

Entrepreneur in ed-tech, building the future of education as a founder and CEO at Playful.

I write about the future of education, designing learning games, and running a startup.

I'm a generalist, introvert, gamer, and optimizing to be useful.

How to find meaningful work

This guide will help you find a project, a job, or a career that fits your needs. But it’s not just about landing a better job. It’s about finding what is meaningful to you and then making a living around it.

There are 10 exercises divided into 4 days that will take you from understanding what you want to a new work-life design you can put into action immediately.

Content

1: Understand what you actually want

2: Find what you enjoy

3: Build work-life prototypes

4: Design bulletproof experiments

Start here

How did we get here

For most of human history, the purpose of work was obvious – to survive. But today, for many of us, this purpose is mostly taken care of by modern civilization. And we struggle to replace the meaning of our working lives once we have enough to make a comfortable living.

We can do anything, want to do everything, and we are lost in between. We wish to be needed, to belong, to be useful. And our culture offers work as a way to be all of it. Work is the capitalist engine for fulfillment.

But to find meaningful work isn’t something taught at school. The world changes faster and faster and we are left to find the meaning of what we do on our own. There is no magical wisdom that would instantly fix our dissatisfaction. It’s a skill we need to learn. And like any other skill, we have to do it over and over to become better at it.

This guide will help you to learn the skill of how to find meaningful work.

I started writing this as an act of necessity from myself to myself. It’s an outcome of my own never-ending struggle to find meaning in what I do with my time. I figured it’s not going anywhere anytime soon, so I better create something to fight it whenever it comes back. Because it always does.

So I put together a framework of ten exercises designed to help you find a work that fits your needs and personality. It takes you through a process of guided self-reflection, followed by pragmatic planning. There are step by step instructions with occasional examples to help you go through the process as smoothly as possible. (Spoiler alert: It’s never smooth.)

On the first day, you will dive into a quest of finding what you truly want. Then you will explore what you enjoy doing and what you are good at. On the third day, you’ll put it together to assemble specific work-life scenarios you could pursue. finally, you’ll design an experiment that will help you safely move towards your newly designed work-life.

How to use this guide

The ten exercises are divided into four bigger chapters named Day 1 to 4. Each part takes a lot of time and energy, so I recommend you to take it slowly, and do them over more than one day. You can approach it literally, and do one chapter a day for four days straight, or in any way that works best for you.

What I don’t recommend, is trying to sprint your way through it in one long evening. The ideas you’re going to wrestle with deserve your sharpest state of mind, and some sleep in between them will do much of the mental heavy-lifting you’re going to need.

(While I procrastinated finishing this guide I designed worksheets you can print and use for these exercises. But they aren’t an essential component. Blank sheets of paper will do the job as well.)

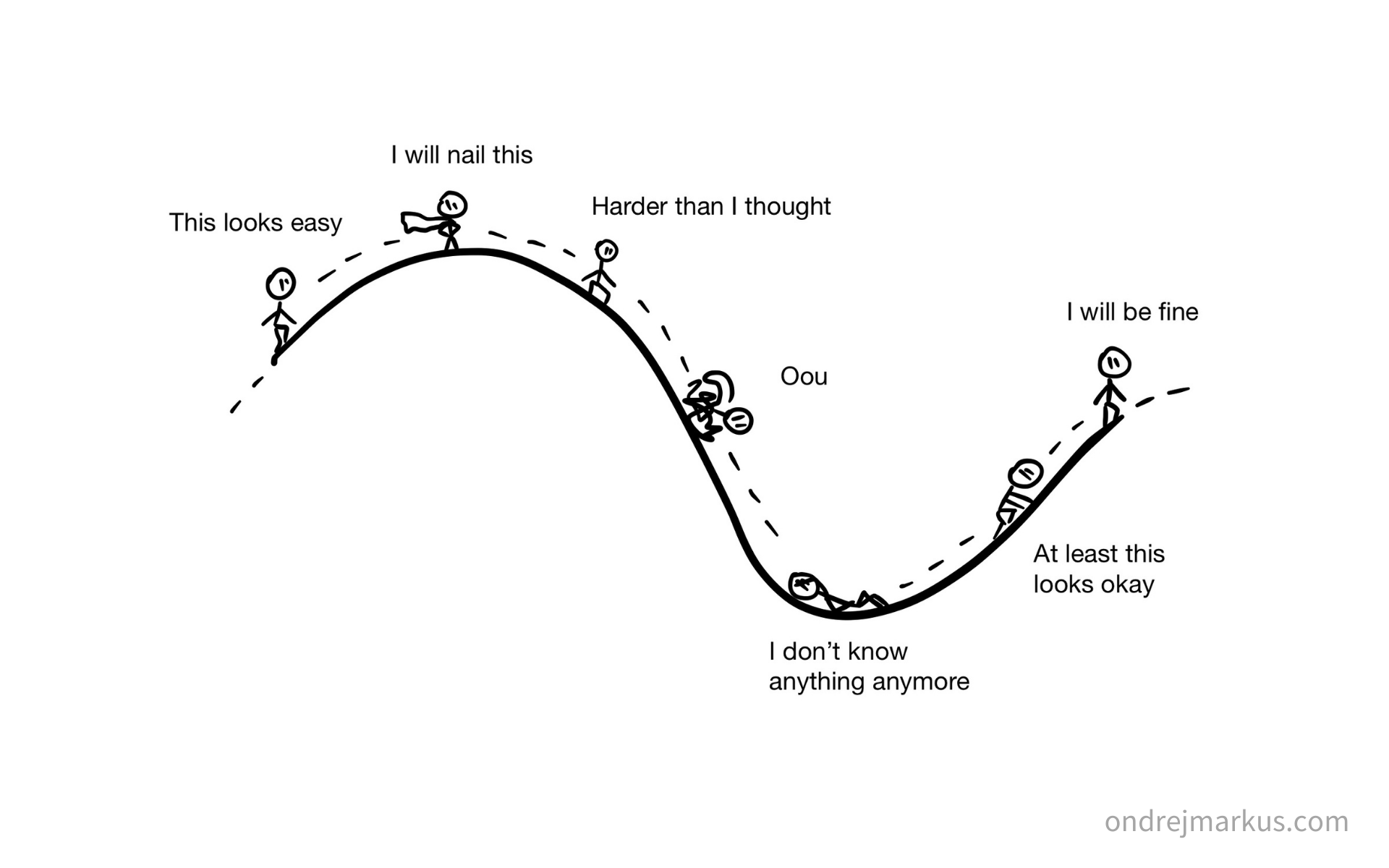

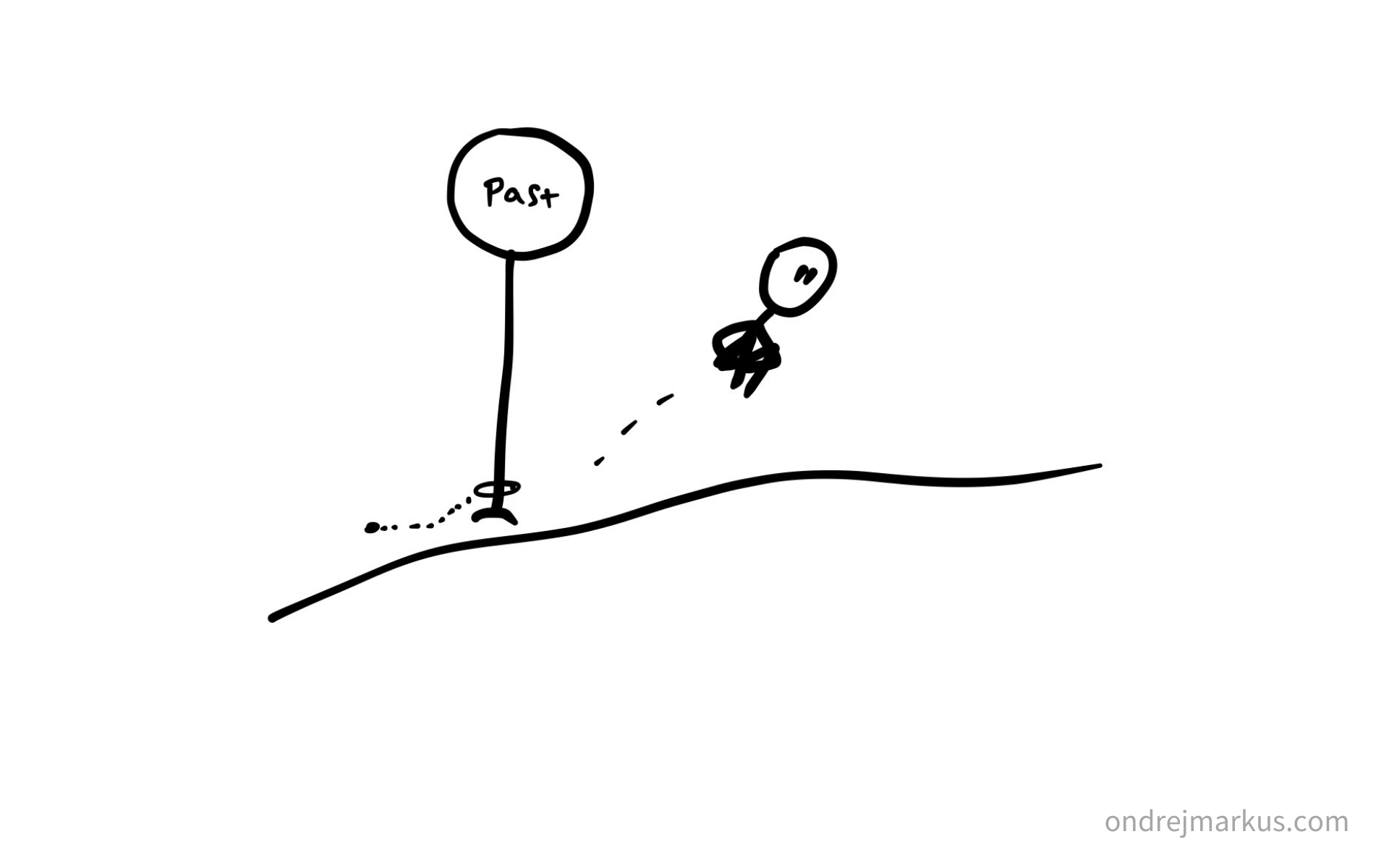

To uncover major life insights isn’t an easy straightforward activity. When you work your way through these exercises day by day, you may feel like this.

It’s dark in the pits of self-reflection, and we never come out the way we entered. When you get confused or anxious exploring your mind, remember that it’s natural. You’re doing it right. We strive for self-knowledge and that lies out of our comfort zone. It takes a lot of courage to begin the process, and even more to finish it.

We need and should put more time into choosing our work-life. We spend days or weeks on deep research when we’re picking a car or a phone, yet we invest so little time into thinking about how we want to spend the rest of our working life. All we need is a pen, paper, and some alone time. We owe this to our future selves.

Understand what you actually want

When anyone asks me “What do you want to be?” I smile on the outside but panic on the inside. I couldn’t possibly reveal the contradictory mess in my head in public. So I deflect with a nervous laugh and spin the conversation to a safer place with a joke or a sudden change of topic. (Uff, that was close.) Next time, I better have some prepared statements memorized.

Longings are anything we desire for reasons both good and bad. It’s what we long for = what we need, want, or value. It’s what we can’t live without (needs), what we would like to have if possible (wants), and how we would like to live (values).

Discovering what we long for is the first and most important step on our way to find meaningful work. What we want is where it all begins, and where it ends. It’s why we do what we do. And to know how to find it and name it is one of the most useful skills we can learn in life.

In the first exercise, we’ll use a simplified framework of three layers of longings to make the search easier. Pick up paper and pen; it’s thinking time.

Step 1: Layers of longings

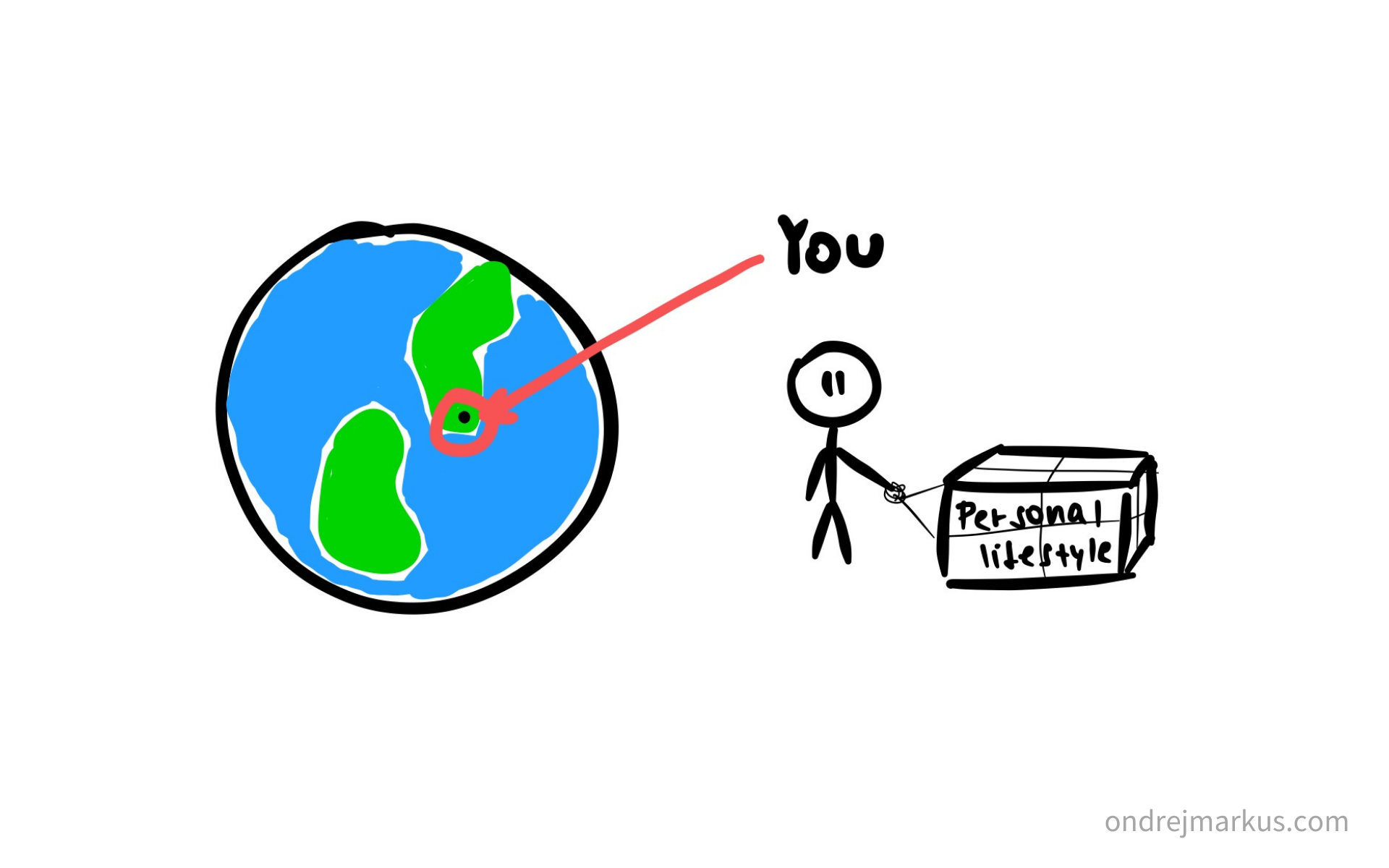

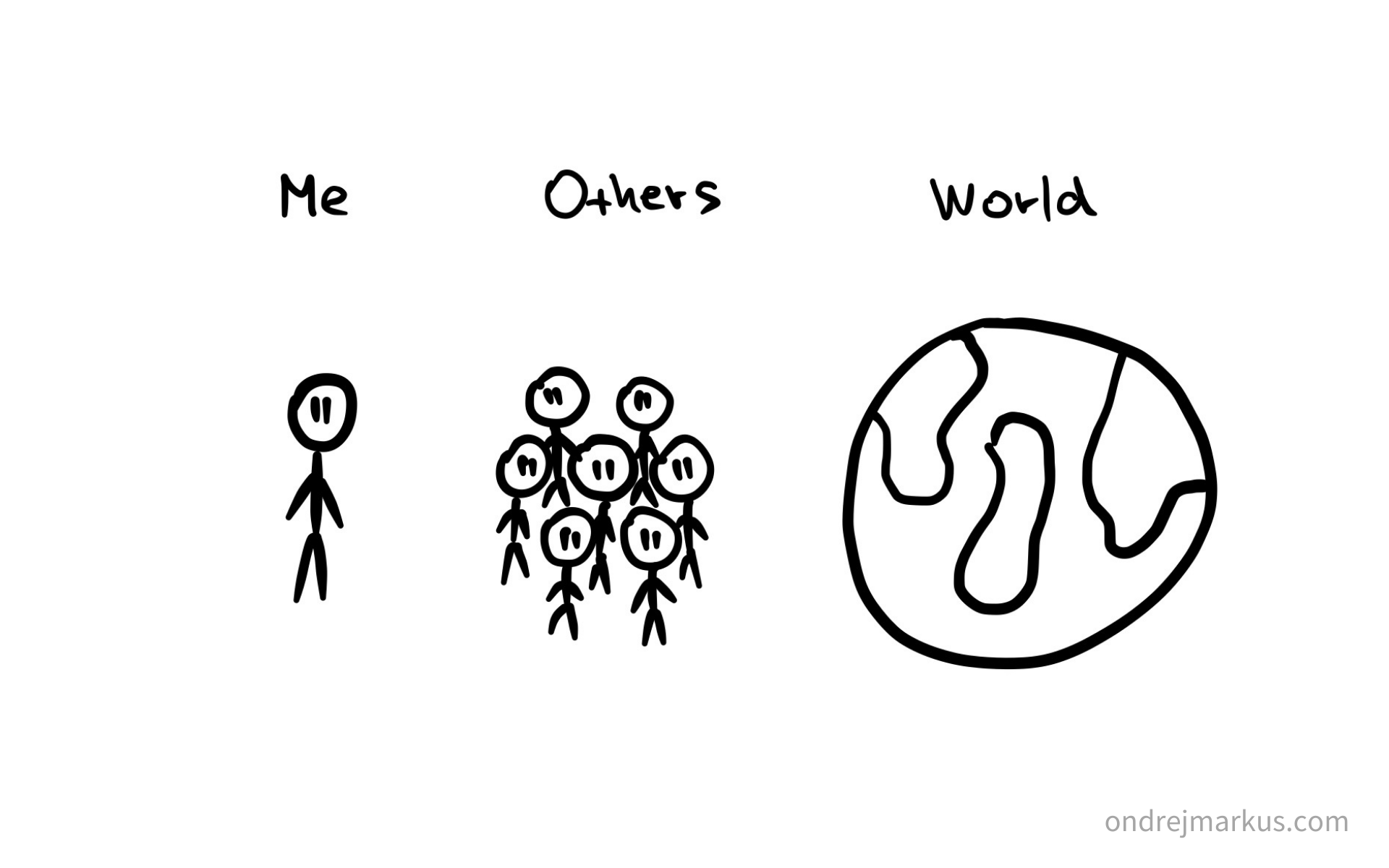

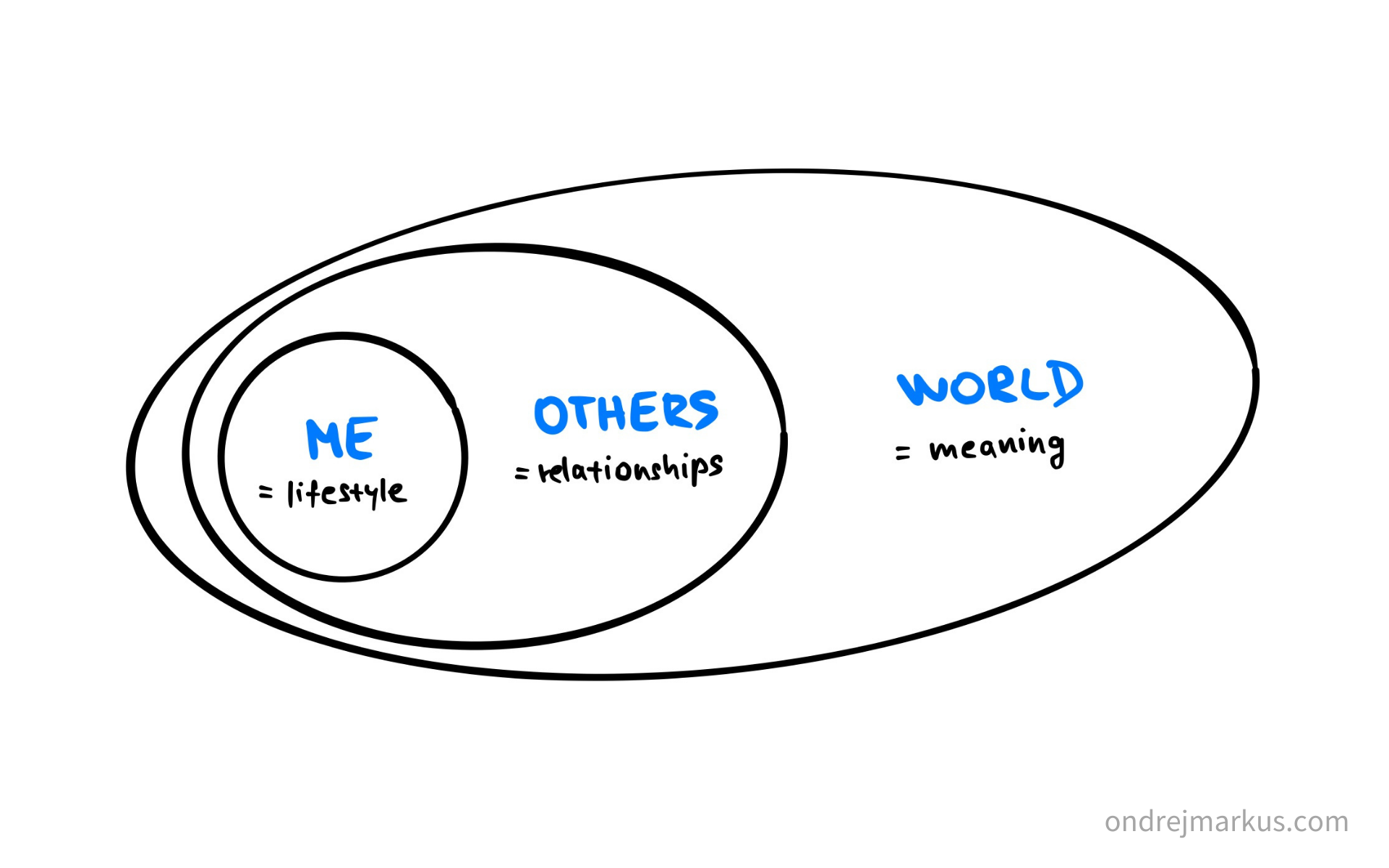

Our goal is to find and name our longings – what we need, want, and value – as accurately as possible. We will imagine longings on three connected layers. The layers are categories of longings based on the context in which we perceive them in our life.

And how they are connected.

We’ll start with our lifestyle (Me), and work our way through our relationships with Others, to the wider context of the World and how we fit into it.

When you write down your longings, remember that you are describing your current state of mind. Your longings will change in time. So the ambition isn’t to get the perfect image of them. It’s enough to make a first draft that we know is going to change. It means we are not afraid to write something today, just to rewrite it in a day or a week. Things change, we change, and our longings change with us.

What most of the exercises are, is little more than thinking out loud on paper. We aren’t creating a piece of art to put on a wall. We experiment, brainstorm, draft, sketch, discard and remake again and again. This is neither place nor time for perfection. Roll up your sleeves, and give yourself permission to write the first longing that comes to your mind.

Use worksheet: Step 1: Discover layers of longings

Me – Personal lifestyle layer

In the layer of lifestyle, we look for anything essential to how we want to live our life.

The lifestyle layer contains longings for practical things like owning a house, finishing school to get a master’s degree, or being physically and mentally fit. But also more high-minded abstract ideas like the freedom to do what we want, to achieve a balance between work and personal life, or to reach an overall peace of mind and happiness.

We have different definitions of what they mean, or we don’t even know what exactly they mean to us, and that’s fine. Most of them are imperfect word-based representations of feelings. So the words themselves are only useful as a reminder we write on paper or play within our head.

After you write them down, it might look weird to have them next to each other, but most of them have a lot more in common than is visible at first sight. Maybe, you can follow the tracks from the longing to own a house, to the need to feel safe and secure, and further to a desire to experience feelings of ease, and to be free from the non-stop worrying.

Try to follow your longings to the core ideas behind them – to the more abstract ideas on the deeper level of feelings. But don’t discard the pragmatic wishes that lead to them. Those are the specific and more actionable longings through which you can reach feelings like peace or freedom.

When you can’t think of anything else to add, move onto the next layer. You can always go back.

Others – Relationships layer

Here we contemplate our connections to others. We are defined by our relationships more than we think. The closer people are to us, the bigger is their influence on us. Family members, romantic partners, friends, co-workers, and strangers.

What do we long for in our relationships with them? Most of us want to belong to a community, to be recognized by others for our unique talents and personality, to be understood, and to get approval for our actions and opinions. And for better or worse, we long for fame, status, and respect from our peers.

It’s possible, that some of the longings you came up with within the lifestyle layer belong in the relationships layer. It doesn’t matter as long as they are somewhere. The purpose of the layers is to guide us through the different perspectives of our longings to spare us of the overwhelming avalanche of thinking about everything at once. Even with them, it’s hard not to get confused, and even if you do, don’t worry. As someone once said: “If you aren’t confused, you just aren’t thinking enough.”

World – Meaning layer

You now have a better idea about what it is you want in your lifestyle and relationships. We continue to the most abstract and confusing layer of all. We’ll look at our place in the world and think about meaning.

What do we want to be in the context of the world?

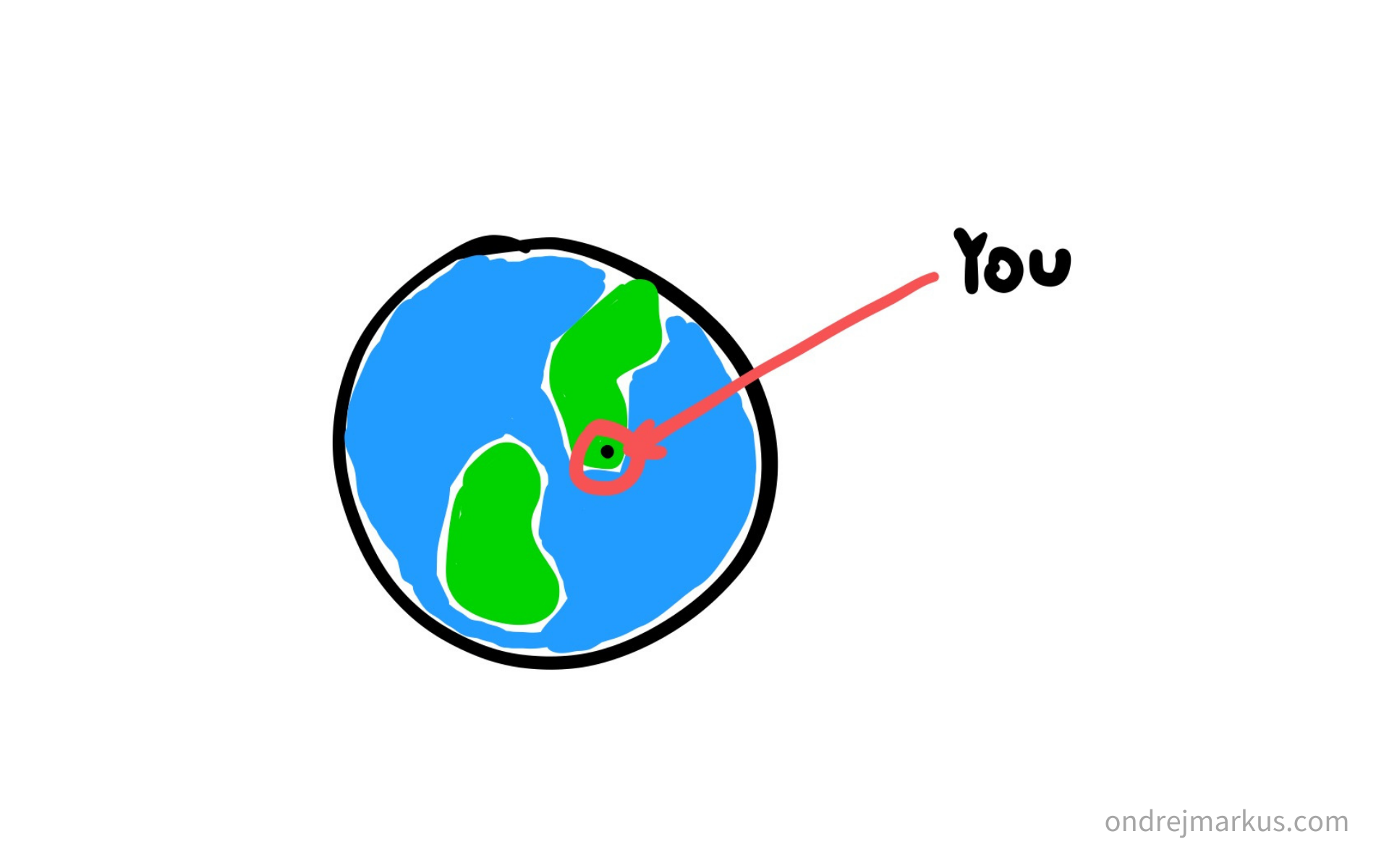

Before we fall into an existential breakdown, let’s look at what we mean by the world. (Warning: It gets weird in the next paragraph.)

The world represents everything around us. We are here and we don’t know what to do. In the context of the universe, we are a blop of nothing; yet strangely, to ourselves, we are everything. Or at least we are to ourselves the only thing we can be somewhat sure about. So when we think about our place in the world, we look for meaning in what we are and do. And only we can decide, what meaning the world has to us.

Others can suggest meaning, and they will, but ultimately, no one controls you, and the meaning you accept is the meaning you live with and for until you change your mind.

So what is the meaning? Is it to leave a legacy for those coming after us, to support a family, to provide enough for those close to us? Is it to make good art, to contribute, to be useful? Is it to have an impact on people now, or to improve the future for later generations? Is it to make sense of all of this and learn how to live – to find the rules of this game of life?

I have my favorites, but ultimately, I don’t know. There is no objective answer I know of, and I suspect there can’t be an objective answer. We have to resolve our preferences, get on with the work, and hope it all makes sense in the end.

If you have no idea how to approach this one, you’re not alone. Don’t torture yourself with it. You have your whole life ahead of you to do that. Instead, if you are stuck, continue to step 2, and come back whenever inspiration strikes you later.

Step 2: Investigate origins

We live our lives connected to other people who influence us, and unless we plan to settle down in a cave to spend the rest of our lives in quiet meditation, we will be continually influenced by them even in the future.

That’s what culture is. We live in our own little cultural bubble and can’t avoid it. We can only try to change the culture in our current bubble, or move into another bubble. Anyway, to be bubbled with others is to be influenced by them.

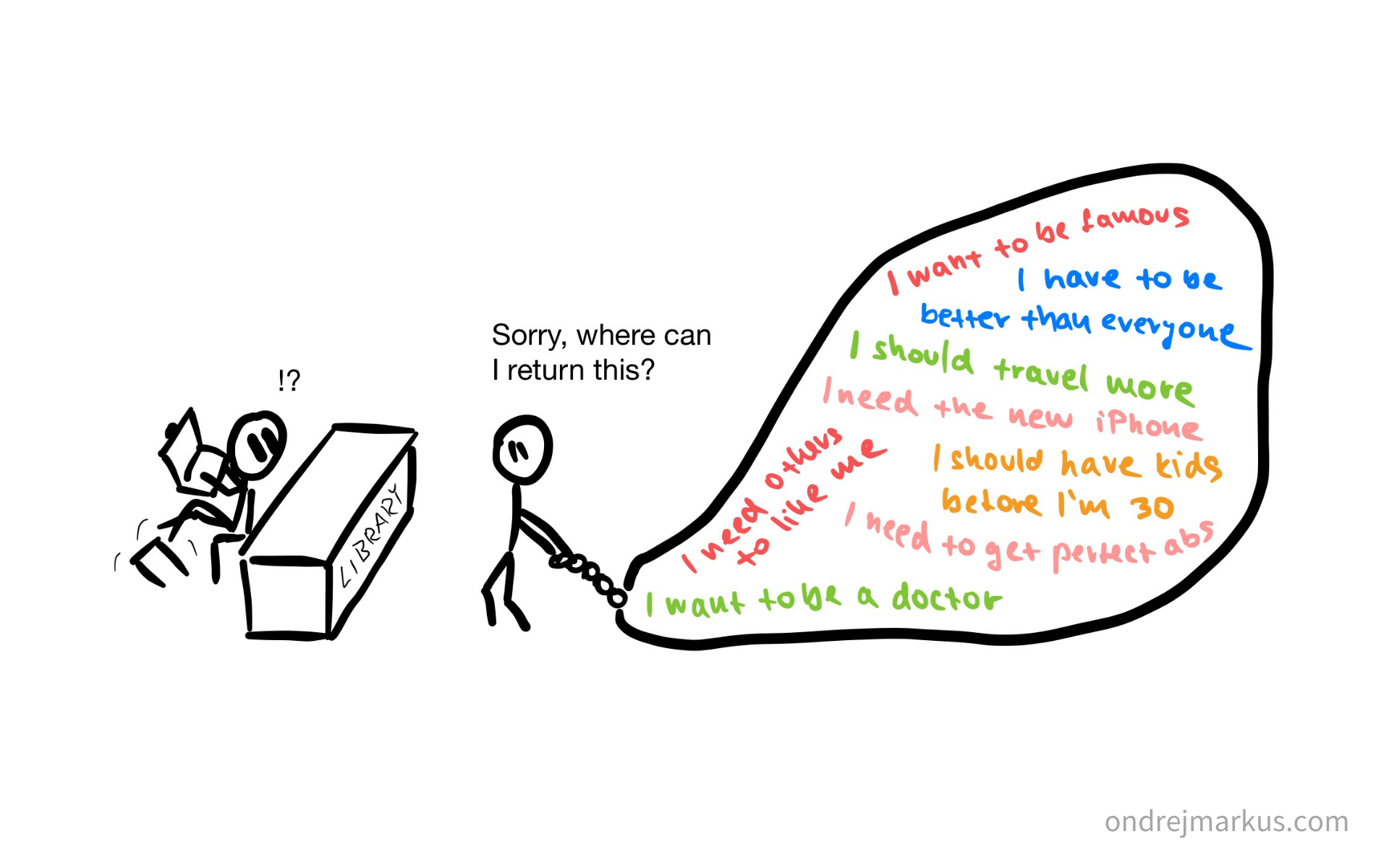

In this exercise, we will investigate which of our longings are authentic, and which are borrowed from others. We’ll give our longings a deeply skeptical look, and buy a ticket to ride the Why train. We take one longing at a time and ask: “Why is this here? Where did it come from?”, and follow the why’s as far as we can remember.

It’s difficult and exhausting. You will get regularly stuck with unclear answers. Don’t give up. None of us are experts in this. But this step is crucial to filter out any intruders in our longings. We don’t want to build our life around things other people want us to want, instead of following what we genuinely want.

To simplify the process, we’ll label our longings by one of the three types of origin: authentic, borrowed, or suspicious.

Use worksheet: Step 2: Inspect origins

Authentic

You went with the why’s and found a moment in your life, where this longing probably originated. You know it’s something you want. It’s genuine and authentic. Cheers.

Borrowed

Here ends up anything, where you discovered a strong influence of someone else as the primary reason you want it. Maybe a well-meaning parent, a friend from the past, or even your younger self. You can thank them and return the longing. You don’t want or need it anymore.

Suspicious

If you’re not sure, put it here. We’ll treat it as authentic for now, but it’s worth revisiting this group in the future, and also to make a mental note to be cautious with them. Their origin isn’t clear.

Remember, we’re not aiming for perfection on our first try. To clarify what’s going on in the big bag of neurons we carry in the hairy ball sticking from our neck is a life long process. If you would have managed to identify just one borrowed longing and got rid of it, it’s a reason to celebrate.

If you think right now what a mess you are. Those thoughts are nothing to be anxious about. Everyone is a mess. We just don’t talk about it.

Step 3: Set priorities

If everything is important, nothing is.

Doesn’t matter if you have a full-stack or just a couple of longings on your list. You need to decide, which ones are the most important to you. And of course, we have categories for that. If you know one thing about me at this point, it’s that I like organizing stuff into categories. And if you think I’d now say “but don’t worry, it’s the last one where we put things into categories”, well, it isn’t.

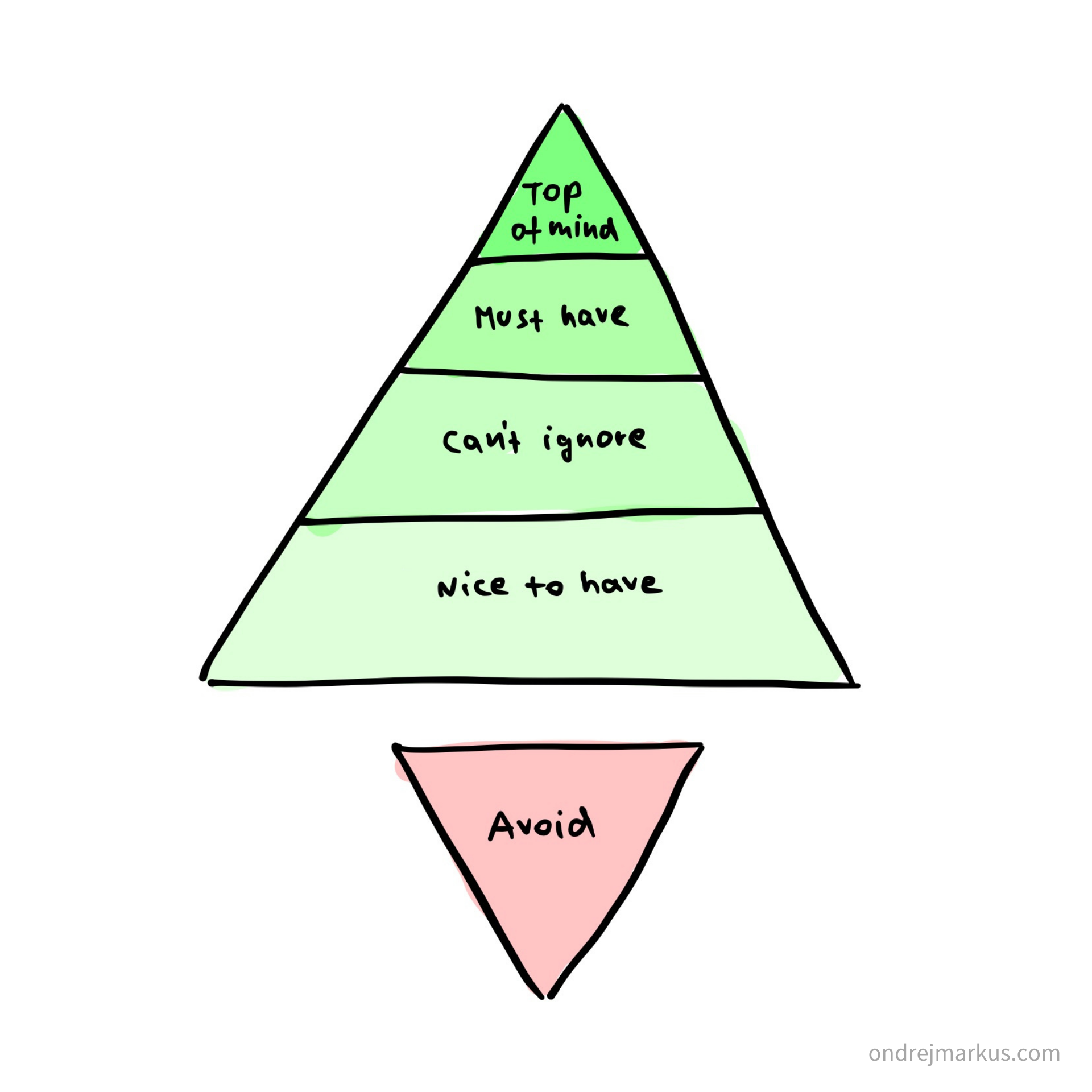

To prioritize them, we organize longings into five levels of importance.

Use worksheet: Step 3: Set priorities

Top of mind

The one thing you can’t put on hold and want to get no matter what. This should be only one thing, or two at most. You think about it all the time. You build your life around this.

Must have

You go hard for these and once you don’t get them for a while, you get unhappy fast. You need them fulfilled to live the life you want.

Can’t ignore

You don’t focus on them, but their absence might cause you trouble over time. You need to maintain them at least at the bare minimum. You can’t fully ignore them.

Nice to have

It’s nice to have them but you don’t actually care about them. They are a pleasant bonus on your way to getting things on higher levels. If you don’t have them, you might not even notice.

Avoid

A special category for longings you don’t consider healthy for you and want to keep your distance from them. Maybe you care a little too much about what others think about you, or you like things just perfect and it’s the reason you seem to never finish anything. It’s your decision what you consider an unhealthy longing. There is no universal measure, only your preference is what matters here.

Your choice

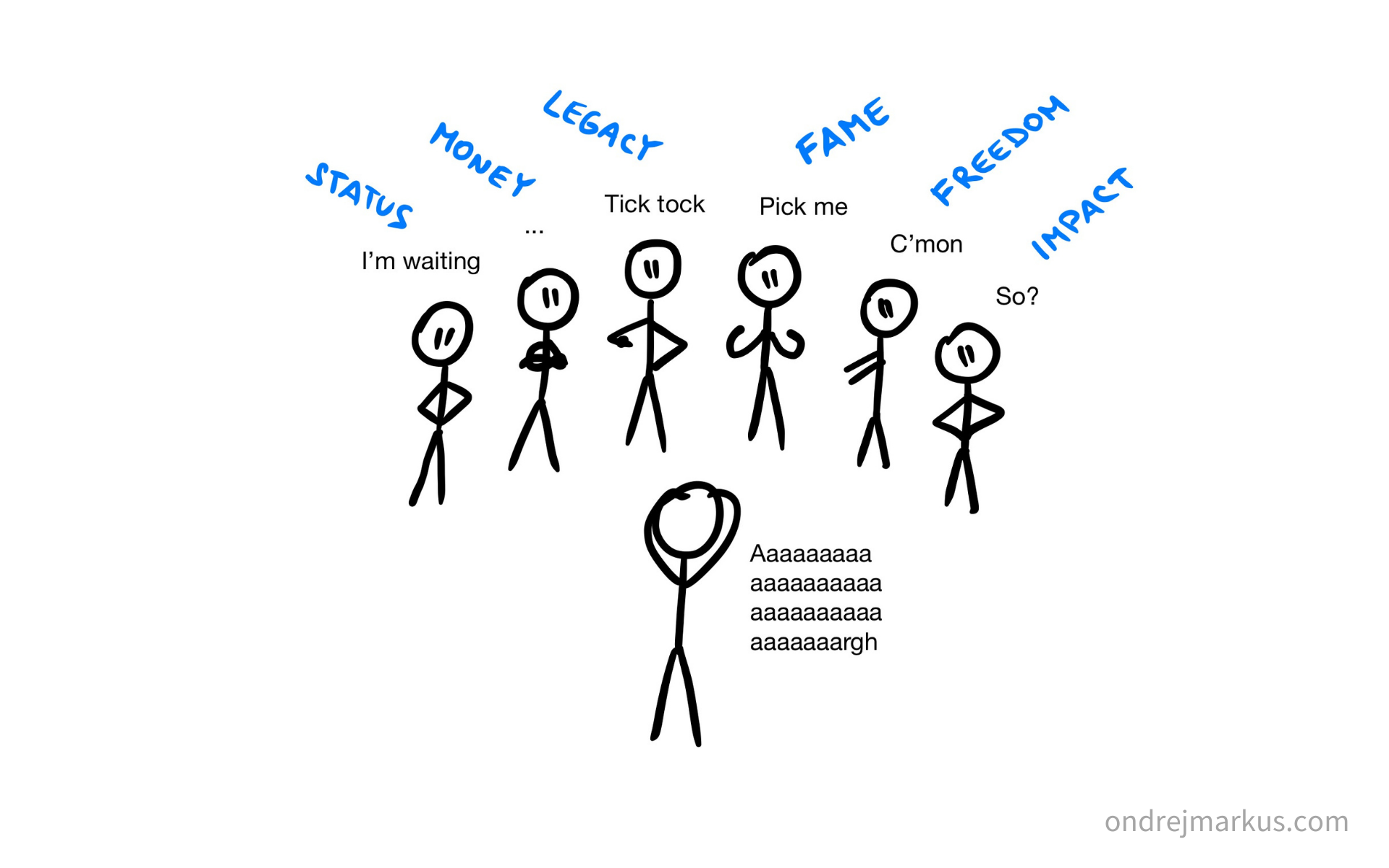

The hard thing about this is that virtually incomparable longings will go head to head against each other, and you will want to get all of them the V.I.L. (Very Important Longing) spots, but there aren’t enough spots. It feels like having an extra ticket to a concert by the favorite band of six of your friends, while you have to give it to only one of them, and the rest of them are looking at you while you decide.

No wonder we often choose not to choose at all and prefer to try to fulfill every one of our longings at once, ending up fulfilling none of them well enough.

Remember, not choosing is also a choice. And usually a bad one.

Find what you enjoy

Focus more on activities than outcomes

Our work culture is built around achievement. In it, we are perceived and judged more by what we’ve accomplished (our semi-true CV), than by who we are and do as a person. When we want to succeed by the rules of this culture, we usually plan our careers or projects around big goals and milestones we need to reach. We plan outcomes first, and then we try to grind our way to them. No matter what it takes.

I think there is a better way to do it.

There is nothing wrong with plans, dreams, and visions. But I burned myself more than once trying to set an ambitious goal with a 10-year roadmap and to then tunnel vision my way to it. Only to soon realize, after the initial hype calmed down, that I am swamped in work I don’t want to do. Visions and plans change often on our way to them, and I don’t want to get stuck in work I don’t enjoy doing day-to-day. Life is too short to wait for better days, while we do things we don’t enjoy.

That’s why focusing primarily on outcomes is a trap. If we give outcomes too much attention, we get easily sucked into the culture of never being enough, and no amount of achievement will ever fill our need to be enough, because there is always more we could do.

To find meaning in what we do, we have to learn to embrace our present state as it is and strive for improvement, not coming from a place of resentment towards our current self, but a deep love of who we are continually becoming.

We have to focus more on what we put into our work (the activity) than on what’s coming out of it (the outcome) because we can control the input, but never the output, as long as the output is judged based on what other people think about it. And it, naturally, often is. Because to be helpful is to serve others, and the value of our actions is in the eye of the beholder. If we do our best and the work is not useful to others, there is nothing we can do about it. It’s not our decision. It’s not under our control.

The only guaranteed thing we can do is to try to be the best version of ourselves right now and do the work. Focus on the activity rather than the outcome.

Joy beats fear

Joy is the best fuel. Unlike fear, it’s fun and it has fewer greenhouse gas emissions. (True story.)

We can use joy to fuel our learning. There is always something new to learn to improve our work, and without joy, the learning process gets painful, therefore the work gets painful.

Sadly, most of the time, we are running on fear fuel. Its main weapon is the deadline. And it works. We get things done under the fear of consequences the deadline imposes. There is no time left to think about whether the work is meaningful to us. We just have to do this thing, otherwise, we don’t get paid, or get ridiculed publicly, or let someone down. We choose a self-oppressive way to live out of necessity to finish urgent tasks.

I’m not saying that deadlines and fear aren’t sometimes useful. They can help us get unstuck and follow through with important responsibilities. What I’m saying is that if I’m not able to finish anything without a deadline, am I really doing the work I want to do?

While growing up, we separate work from play. We convince ourselves or get convinced, they are different things. “Play is what you like and want to do. Work is what you don’t like but have to do.” But does it have to be that way?

Sure, I could finish my dissertation on artificial intelligence in healthcare in the last 48 hours before the deadline while running on fear fuel, but how stressful is that? Wouldn’t it be easier to switch to joy?

Kids don’t need a deadline to finish a lego castle. They do it out of joy. But that doesn’t mean they don’t have to work for it. It’s a challenge to do it, therefore not everyone can do it, and that’s how they create value through their abilities.

That’s what useful work is: using your strengths to create value others can’t.

Easier said than done, I know. The world isn’t perfect. We need to make a living and work with what we already have. But what if we could do at least a bigger part of our work out of joy rather than fear? Would you want to?

Step 4: Find your joys and strengths

Joy is at the core of what we are looking for. It’s a powerful engine for meaningful work, and once we learn to set it up, it can take us to any outcome we want.

We’ll search for what we enjoy and don’t enjoy, what we are good at and bad at. Together, they’ll create a map of work-life options we could pursue to fulfill our longings through work.

Thinking about joys in the context of work isn’t natural for most people. Don’t worry, if it’s difficult for you at first. If no particular joy comes to your mind, just begin by listing what you hate to do, and you’ll be off to a great start. Also, there are some guiding questions to help you in every section.

Finding joys isn’t just about activities, but also about how we enjoy being. For example, do you prefer working in a team, or alone? Do you like precise logical work or more uncertain creative work? Do you enjoy quickly changing tasks or complex long-term projects?

Use worksheet: Step 4: Find joys and strengths

What do you enjoy?

- What do you do for fun? - What do you enjoy talking about? - What did you enjoy doing as a child? - What parts of your current work do you enjoy?

What you don’t enjoy?

- What makes you bored quickly? - What activities do you dislike in your current work? Our next move is to examine our strengths and weaknesses.

What are you good at?

- What can you do better than most people around you? - What strengths do you use in your current work?

What are you bad at?

- What most people around you can do better than you? - What are the weakest abilities you have to use in your current work?

Important: Ask other people

We are not capable of seeing ourselves 100% objectively. To get a more accurate picture of your strengths and weaknesses, ask people who know you and work with you what they think.

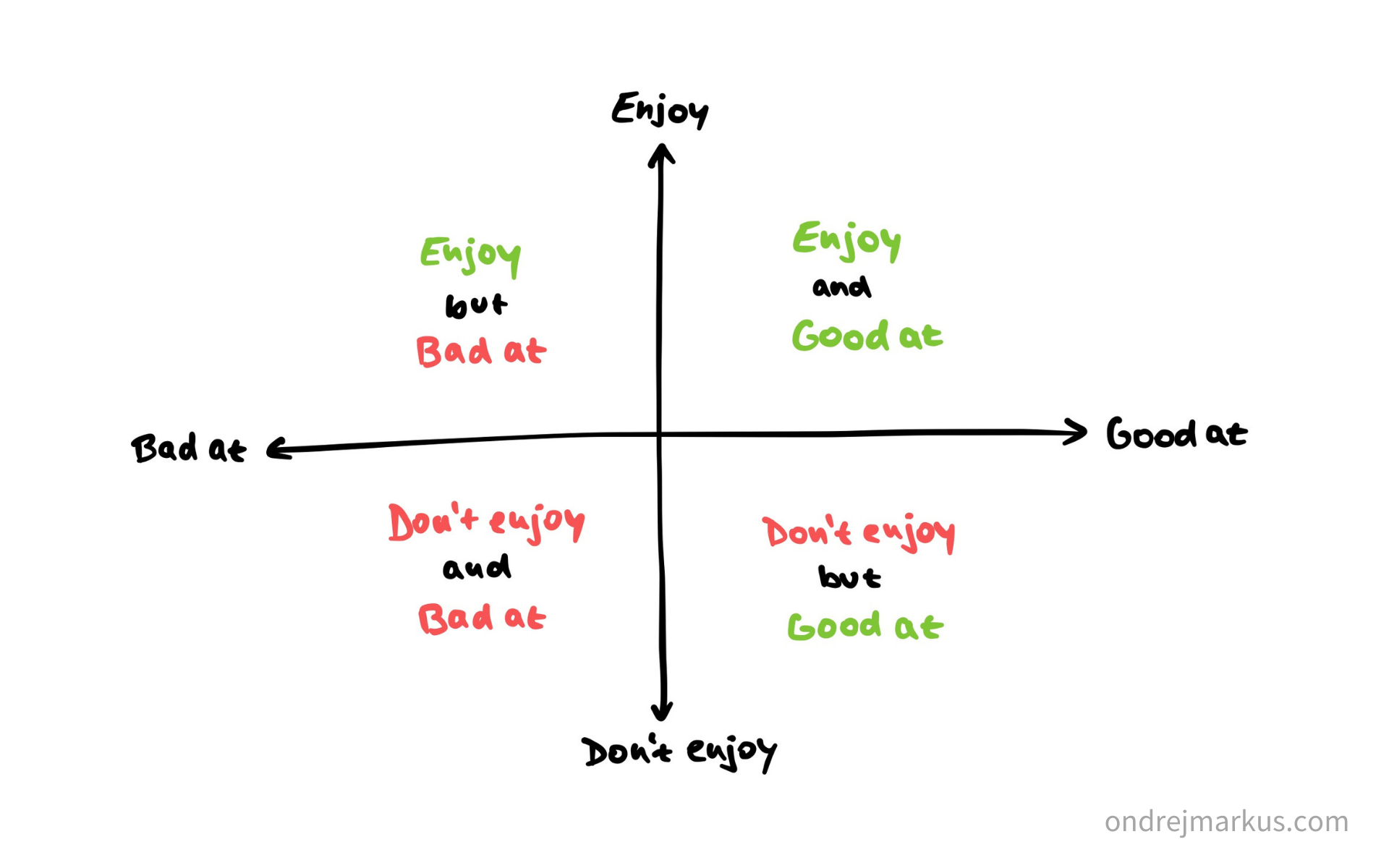

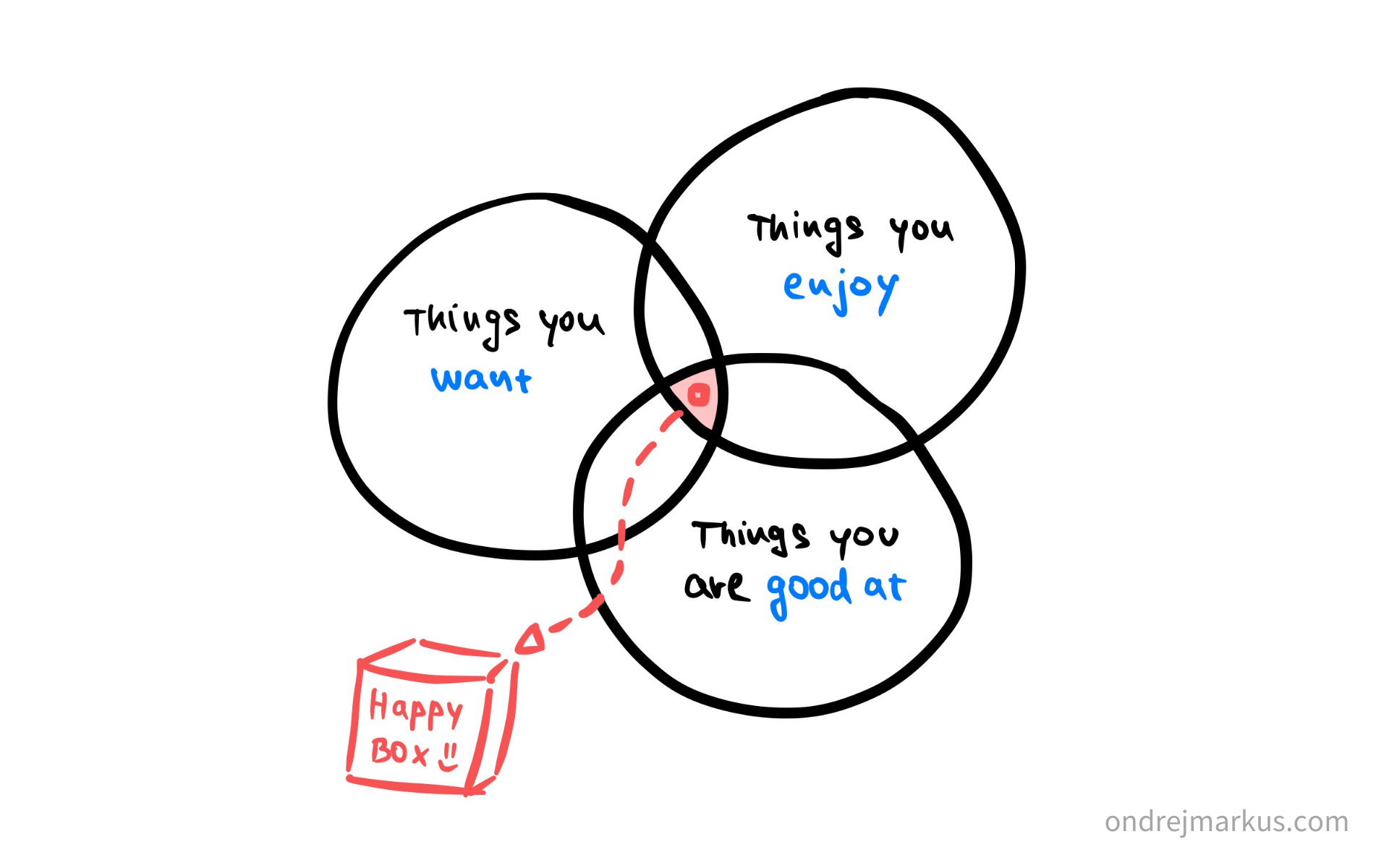

Step 5: Detect overlaps

This is where we put joys and skills together to create a map. We identify which joys and strengths overlap with each other–which of them are in some way connected or similar.

Doing this will bring new insights into your current work-life, and it will shed more light on what do you want in your ideal work-life. Connecting joys and skills on an axis create a quadrant that is split into four sections. Look at what you wrote down in step 4 and find connections.

Use worksheet: Step 5: Detect overlaps

Enjoy and good at

The things you excel at and enjoy doing. This is the gold we are digging for.

Maybe you enjoy interacting with people, while you also have good people skills. Or you like to create things from scratch, and writing code enables you to do just that.

Enjoy but (currently) bad at

These are usually things we are curious about and enjoy talking about, but never gave them proper time to develop the skills we need for them to work. They are the best learning opportunities.

It’s the passion for music that you’ve never pursued properly, even though you could talk about it any time it comes up. Or you’re pulled in by web design, but don’t yet know what is the coding stuff all about.

Don’t enjoy and bad at

It’s a pain to have these in our current work, but, naturally, some portion of them will be from this quadrant.

Maybe you don’t like doing paperwork, but still have to do the bare minimum like sending out invoices every month. If your work consists mostly of this quadrant, you should change that as quickly as possible.

Don’t enjoy but good at

This is a trap. Because you are good at these, you will be asked to do them. And because you are good at them, you probably will do them. Before you know it, your schedule is full of tasks and activities you don’t enjoy doing, even though you are great at making them happen.

It’s that one time you’ve agreed to organize a teambuilding retreat, did a great job despite hating it, and now you’re stuck on organizing it every time with no idea of how to get of out of it.

Build work-life prototypes

Work to live, don’t live to work

We can’t separate work and life, at least not entirely. Anything we do in life affects everything else. That’s why we view work as an inseparable part of life and use the concept of work-life as what we design here.

Work is part of our lifestyle, it affects our relationships, and it’s one of the ways to create value and gain meaning.

Step 6: Assemble the Happy box

The Happy box is the place where your longings, joys, and strengths connect. Any scenario inhabiting the Happy box will employ your skills fueled by joy to fulfill your most important longings in life.

When you start assembling your Happy box, focus primarily on your top of mind and must have longings, and where what you enjoy doing connects with what you’re good at. Together, they form a compass for finding the treasure that the Happy box is.

Write down what the longings, joys, and strengths are, and assemble your Happy box. If your Happy box is well-calibrated (its content has authentic origins), your newly found work-life is going to be meaningful and fulfilling for you on every layer. It will offer the personal lifestyle you desire, support functioning relationships in your social bubbles, and deliver the meaning you seek in your daily work-life. What is inside your Happy box?

Use worksheet: Step 6: Assemble the Happy box

Until now, we had our heads in the clouds, thinking about what we want and don’t want, like and don’t like. In the next step, we’ll work towards a specific real-world scenario build from what’s inside our Happy box.

Step 7: Visualize work-life scenarios

We’ll look again at our Happy box and visualize real-world scenarios, that could be made from its insides. To imagine possible work-life scenarios is like having ingredients and create recipes, that would best combine them into a delicious meal.

However, it would be too good to be true to find a work-life that employs 100% of our Happy box and contains nothing else that might annoy us – some boring tasks and unwanted responsibilities we didn’t ask for. There is always something we don’t like to do in any work-life. And if there isn’t at first, our brain will quickly make something up to be unhappy about. That’s its job.

We are realists here. So when you visualize scenarios, keep in mind, it’s good enough to find the ones that are mostly made of your Happy box, but it’s okay to let in some unwanted parts.

Also when you visualize your work-life, don’t include just the work part, but describe any parts that are important to you (based on your longings).

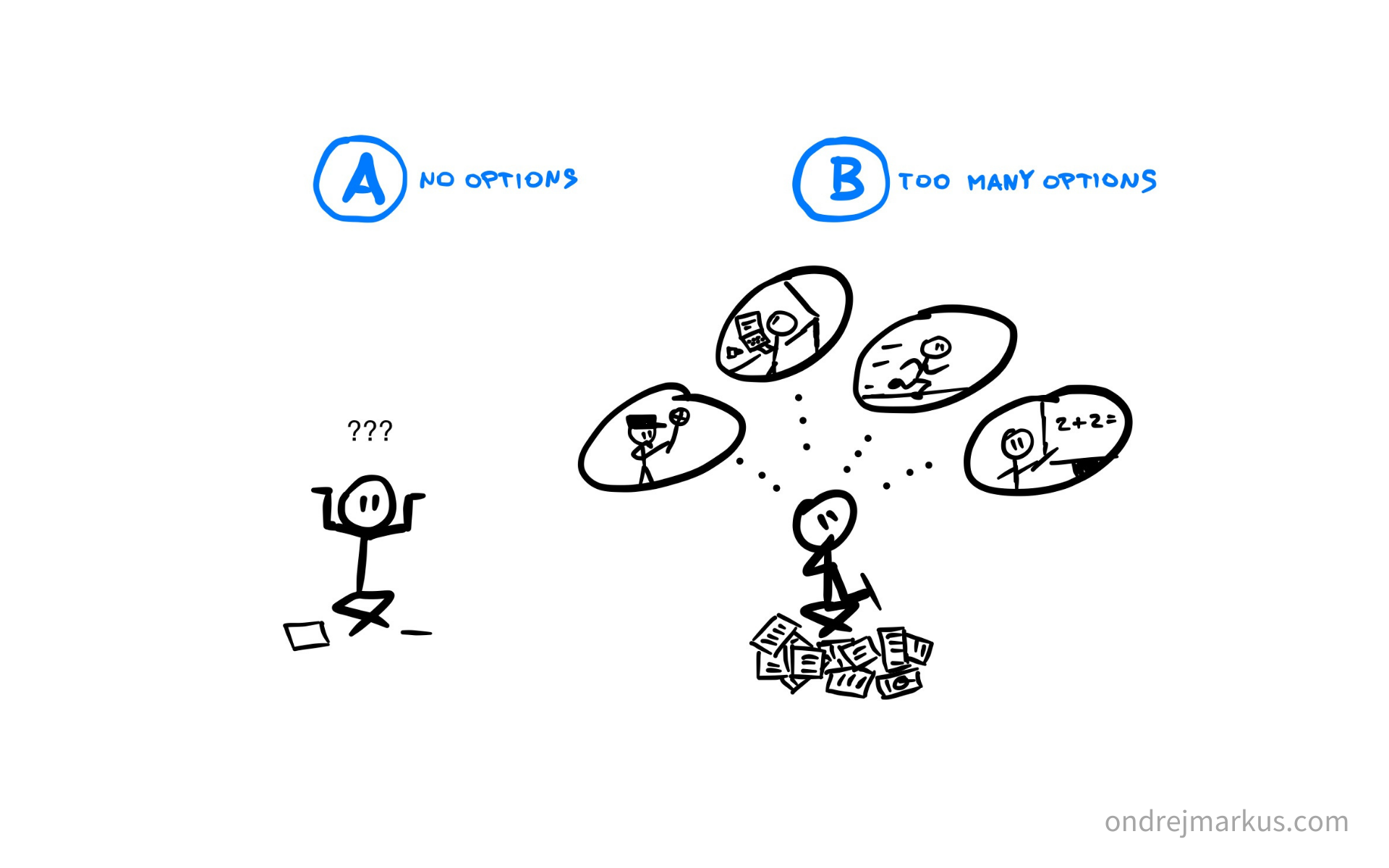

If you struggle to choose a scenario to write about, you might be experiencing one of these situations:

Start small and go from there

Maybe it’s overwhelming for you – the volume of what you need and want. Maybe you aren’t used to big changes, and frankly, you don’t even like them. That’s totally fine. To make things more comfortable, just imagine what your current work-life is, describe it in words, and then add changes that would improve it.

Fight the fear of missing out

Because you read this guide, it means you have the opportunity to do and learn almost anything you want (you have access to the internet) and that sheer amount of options feels paralyzing. You are constantly under pressure to choose only one thing and leave everything else on the table.

To allow yourself to choose, think about it as picking the next thing you want to try. You don’t commit yet. It’s just the thing that interests you the most at this moment, and you’d like to learn more about it.

Use worksheet: Step 7: Visualize work-life scenarios

The first that comes to mind

- Hopefully, with A and B in mind, you are now ready to find an answer: What is the first Happy box work-life scenario that comes to your mind?

If the first one wasn’t possible

- Sometimes, we bet all our hopes on one and only option. And we get miserable if it doesn’t work as we expected.

You’ll visualize this scenario to prove to yourself, there is more than one work-life, which can fulfill your longings and that you’d enjoy. Try to step a little outside of your thinking box, and describe what it could be: If the first scenario wasn’t possible anymore (robots do it better cheaper now, sorry), what else could you do?

Rainbows and unicorns

- Hands up, shorts down. Throw the box out of the window and consider this utopian scenario, even if just for fun. Don’t let your visualization be stopped by the voice in your head that screams it could never work in the real world. You don’t have to actually do it. Just enjoy the ideas of what it would mean to your work-life: If money didn’t exist and no one could laugh at you, what would you do?

Go-to scenario

- Now, think about what you’ve learned from all three of them, and put it together. It might be an updated version of the first one, or it changed with something you discovered when thinking about the one with robots in it. Anyway, keep in mind how to start small and fight the fear of missing out, and pick your favorite one at this moment. What is the scenario you’d like to pursue in your life right now?

The further we get, the more specific and down-to-earth we are.

Sleep on it and then continue to Day 4, where it’s all about putting dreams into concrete plans and action.

Design bulletproof experiments

Don’t commit, experiment first

With your go-to scenario in front of you, you might feel like making some epic changes – quit your job, end business partnerships, or other life-changing actions. But, please, hold your horses. We want to be smart about this and don’t rush anything. To do that, we are going to do some science.

Our strategy is to keep our options open. We don’t want to commit too early or to rush any dramatic changes, which we might later regret. We’ll look at our scenario as a hypothesis.

A hypothesis is an assumption we need to test before we can confirm it’s true. We’ll design an experiment with phases of gradually increasing commitment to planning the transition from our current work-life to the new one, but responsibly and with minimum risk of burning ourselves by being impatient.

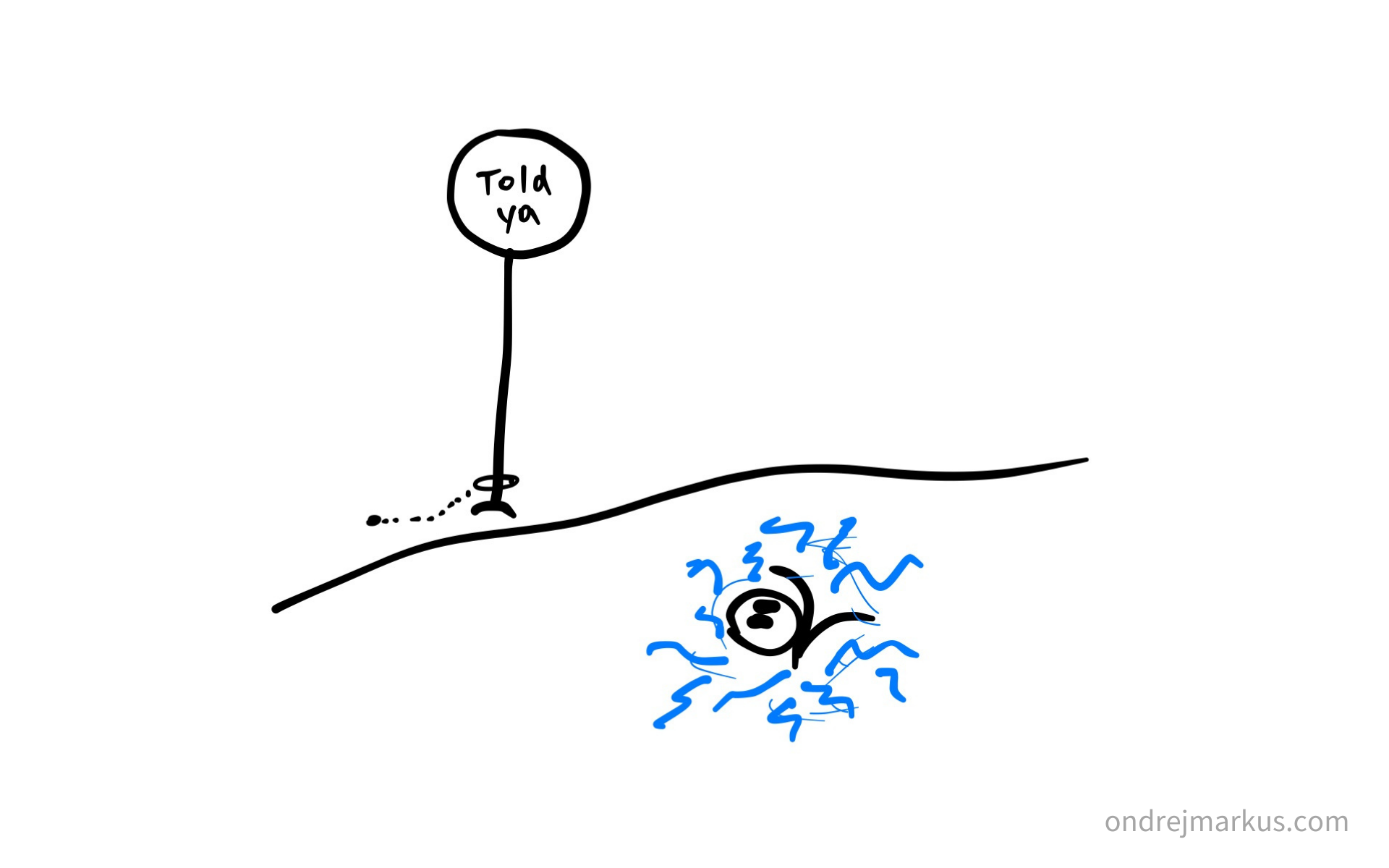

We are cautious because often we want things for the wrong reasons. We think they’ll bring us what we want, but they don’t. Sometimes, it all works out differently than we thought it would, and we end up disappointed, or even trapped in a situation we don’t like. People are bad at making predictions.

The objective of this experiment method is to find out if our scenario fulfills what we expect. And we do it by applying the bare minimum of changes needed, and we constantly observe our feelings and experiences, ready to adjust our plans as needed. We will test our assumptions before we commit ourselves full-time. We’ll design three phases of gradually increasing commitment.

Step 8: Design an experiment

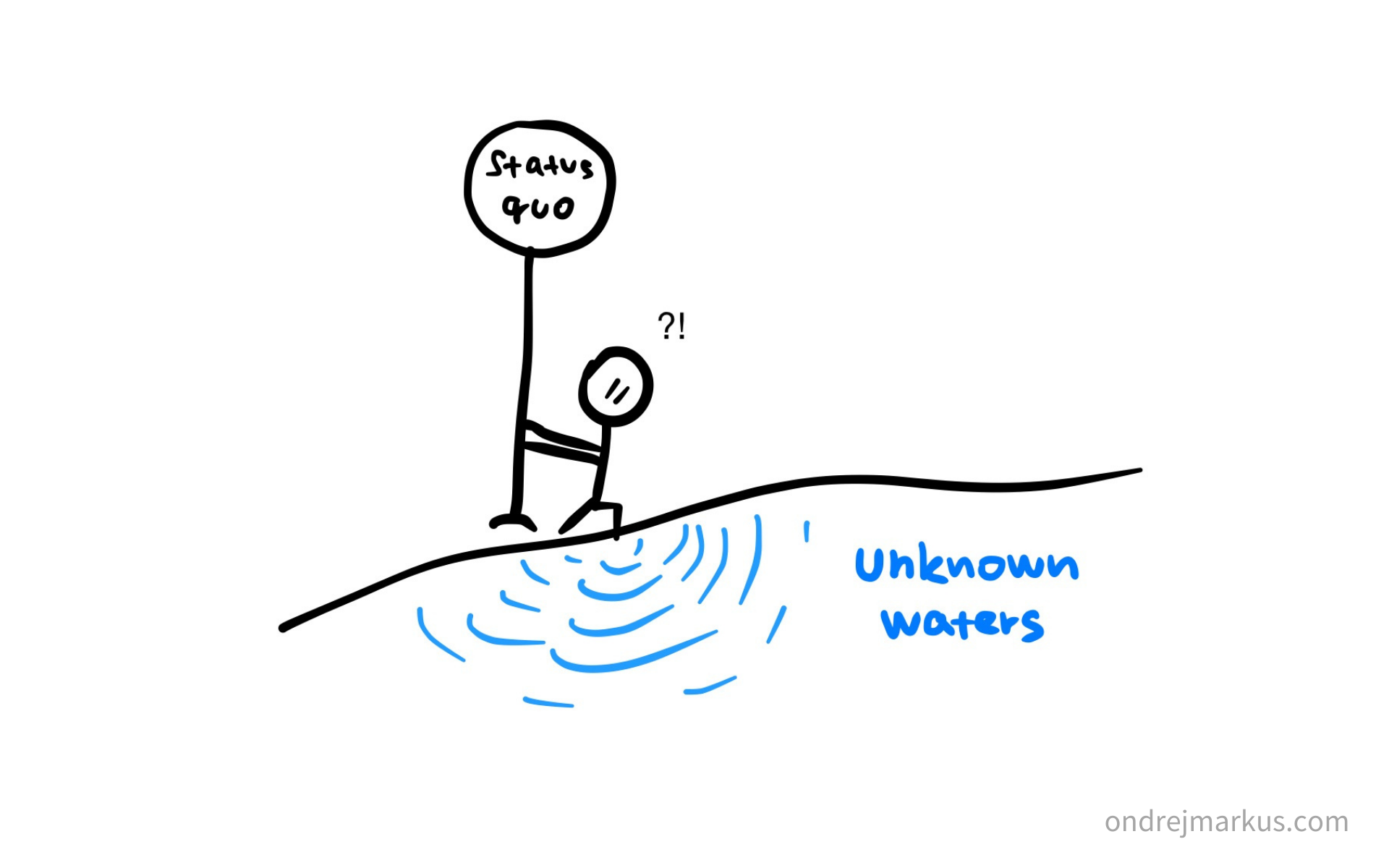

Phase 1: Testing the waters

In the first phase, we stay away from any big changes to our current work-life. We are the kid who was let to run around the toyshop and now we want the shiniest lego set we found, and we want it now.

But, as the adult we are (ehm), we want to know, if we should commit to this one, or if we would get annoyed with it after just a couple of days, and we wanted it only because it was something new.

We need to test our new work-life for potential holes we didn’t see from a distance, but which will be quickly obvious after we step into it.

What can you do to test your new work-life with 30 minutes a day? (In your free time.)

Use worksheet: Step 8: Design phases of commitment

The idea behind this is, that there must be something you can do, or are partly already doing, that is at the core of what you want to do.

For example, if you’d like to write a book, what could you do to do it for 30 minutes a day? And if you aren’t already writing, not even for 30 minutes a day, how sure are you that you would enjoy doing it for more than that? The easiest way to know is to try it and observe yourself.

A lot of the things we enjoy, we are already doing as hobbies. And some of what is a hobby should stay a hobby because there is a difference between doing something just when we are in a mood for it, and doing it even if we don’t feel like doing it. That’s where hobby becomes work. And that’s not a bad thing, it’s just different.

How can we tell which one is it? We can’t, until we move it into the next phase of commitment, and observe if it sticks.

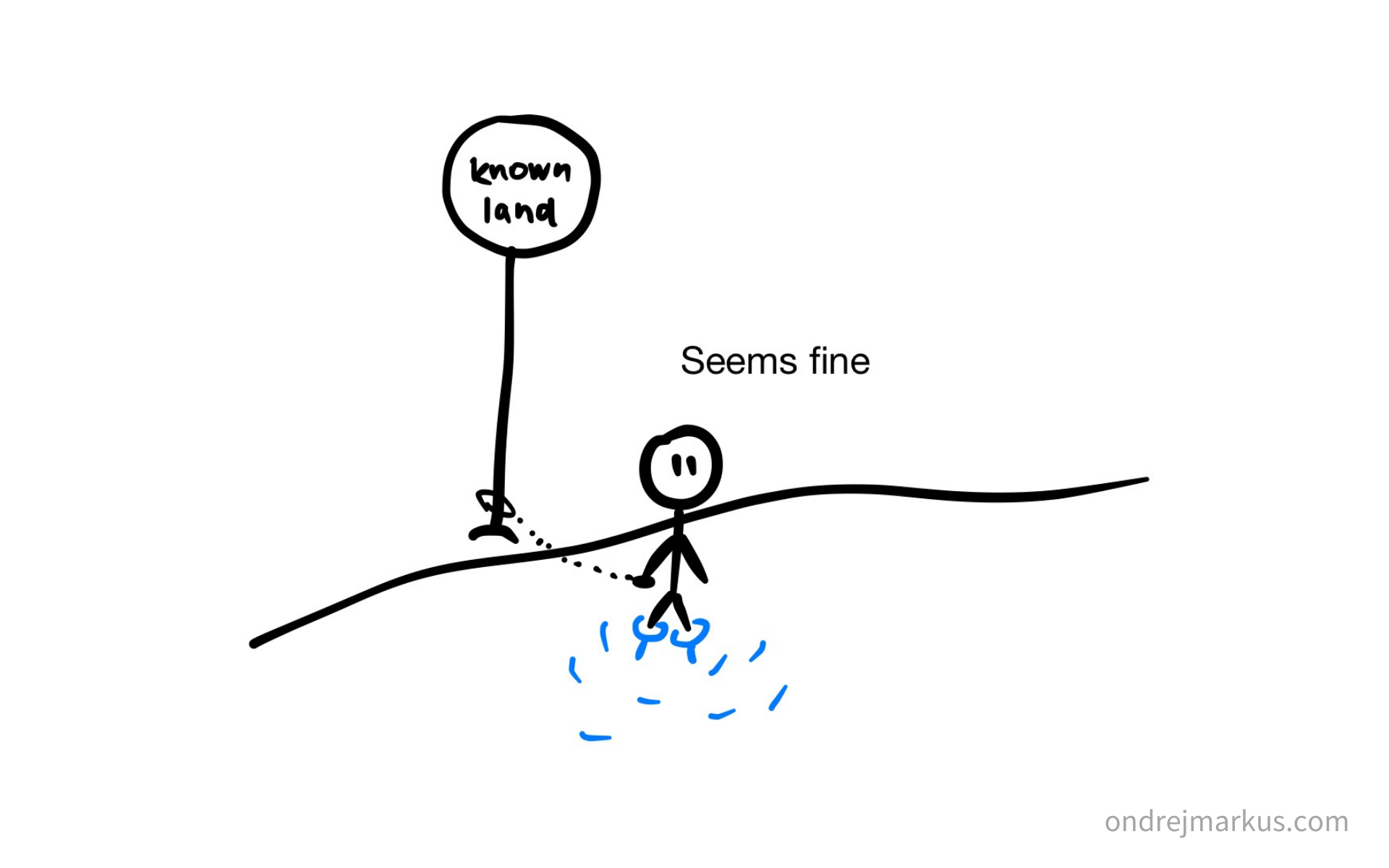

Phase 2: Water under knees

If it feels good in your free time, you enjoy it and want more, it’s a good time to move to the second phase. Here you are ready to make the first real changes to your current lifestyle and create more space for the work-life you want to pursue.

Ideally, we don’t want to jump to the full-time phase just yet but stand in the water for a little while longer to get to know the real taste of it.

What can you do to test your new work-life with 3 hours a day? (Part-time)

For example, if you are trying to start your own business, it might be a smart move to negotiate a part-time deal in your current job and work on your project in the other half of your work-day. It’s less stressful because you don’t need to worry about income stability right from the start. Also, you keep the option to go back to your job, if the whole entrepreneur hypothesis doesn’t deliver what you’ve expected.

I’m aware that part-time commitment isn’t a regular option in most jobs. You might need to get creative with it. If you have a good relationship with your boss, maybe just show your cards – tell her what you have in mind and if she sees any possibilities this could work well for both sides. If you fear that talking about lowering your commitment would mark you as a heretical traitor in your workplace, it might not be worth the risk, and your go-to move is to do the extra work on weekends and evenings. It’s another way to test your commitment.

Phase 3: Jump

This is the real thing. To know what it’s like, you have to eventually try it in the full-time mode.

What can you do to test your new work-life full-time?

Security alert

Right now, your practical side is probably skeptical about this whole situation. “Sure, it sounds nice in theory, but who’s going to pay for the house you want to start saving for? Yeah, and remember those two little humans that depend on your income?”

There are going to be conflicts between your different longings. On one hand, you want to pursue your work as an actor full-time, but on the other hand, the bills won’t pay themselves and there isn’t enough money on your account even for your next rent.

Maybe at this point, you’ll be forced to revisit your longings and review your priorities. Your financial stability might be more important than you first thought, and you can almost taste the fear in your mouth when you think about the earthquake this change of work-life would create. It’s fine. We should view our prioritized longings as an ever-changing draft, and never hesitate to adjust them with the newest information we observed about ourselves.

To keep being responsible about this, and to calm down the security freak in our head, we will do what I call bulletproofing.

Step 9: Bulletproof your experiment

To strengthen our plans, we are going to visualize the first phase with a life-changing impact on our longings. It’s probably the phase 2 or 3, depending on how flexible is your current lifestyle. Phase 1 is usually manageable without changes that would significantly affect your income and relationship stability. If that’s the case, skip it.

We bulletproof the experiment by taking the phase through four visualizations, where we focus on the practical aspects of our life. For most of us, it’s going to be money, because we use work to make a living, and our landlord isn’t going to be sympathetic to our journey for meaning if we don’t send him the next month’s rent on time.

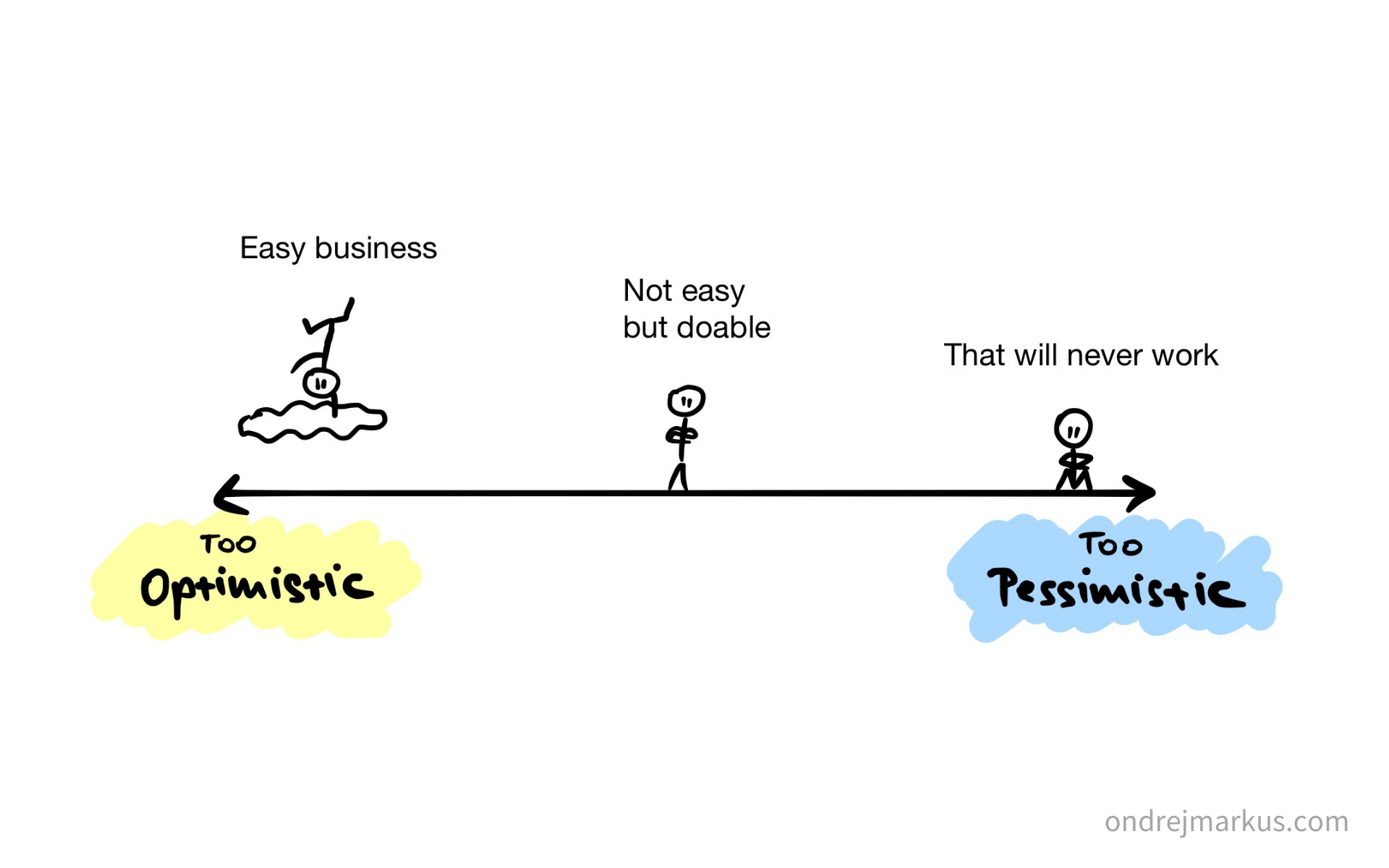

The bulletproofing method encourages us to visualize what will happen more realistically by going through scenarios from most likely, to worst case, to unicorns and rainbows.

The goal of this exercise is to make sure we know about things that could go wrong and think about how we would fix them if necessary. All of us tend to be more optimistic or pessimistic than we should be. So we want to calibrate ourselves to a realistic mindset. Not to underestimate the impact of our choices, but also not to be unreasonable and scared of easily fixable changes that probably won’t even happen.

By doing this, we get a better idea about how to responsibly handle our finances during the experiment, and we are more certain our mental health and relationships will also survive. One by one, write down what you visualize in as much detail as you need to calm down your pragmatic self.

Use worksheet: Step 9: Bulletproof experiment

Plan A = What do you expect to happen?

Plan B = If it doesn’t work like expected, what would you do?

Plan Z = How would you fix the situation, if everything went wrong?

Plan A+ = What would happen, if everything worked 10 times better than you expected?

This was a whole bunch of thinking, planning, and overall axe sharpening. But no change will actually happen if we don’t act on it.

Step 10: Action plan

Walk over the Maybe Bridge

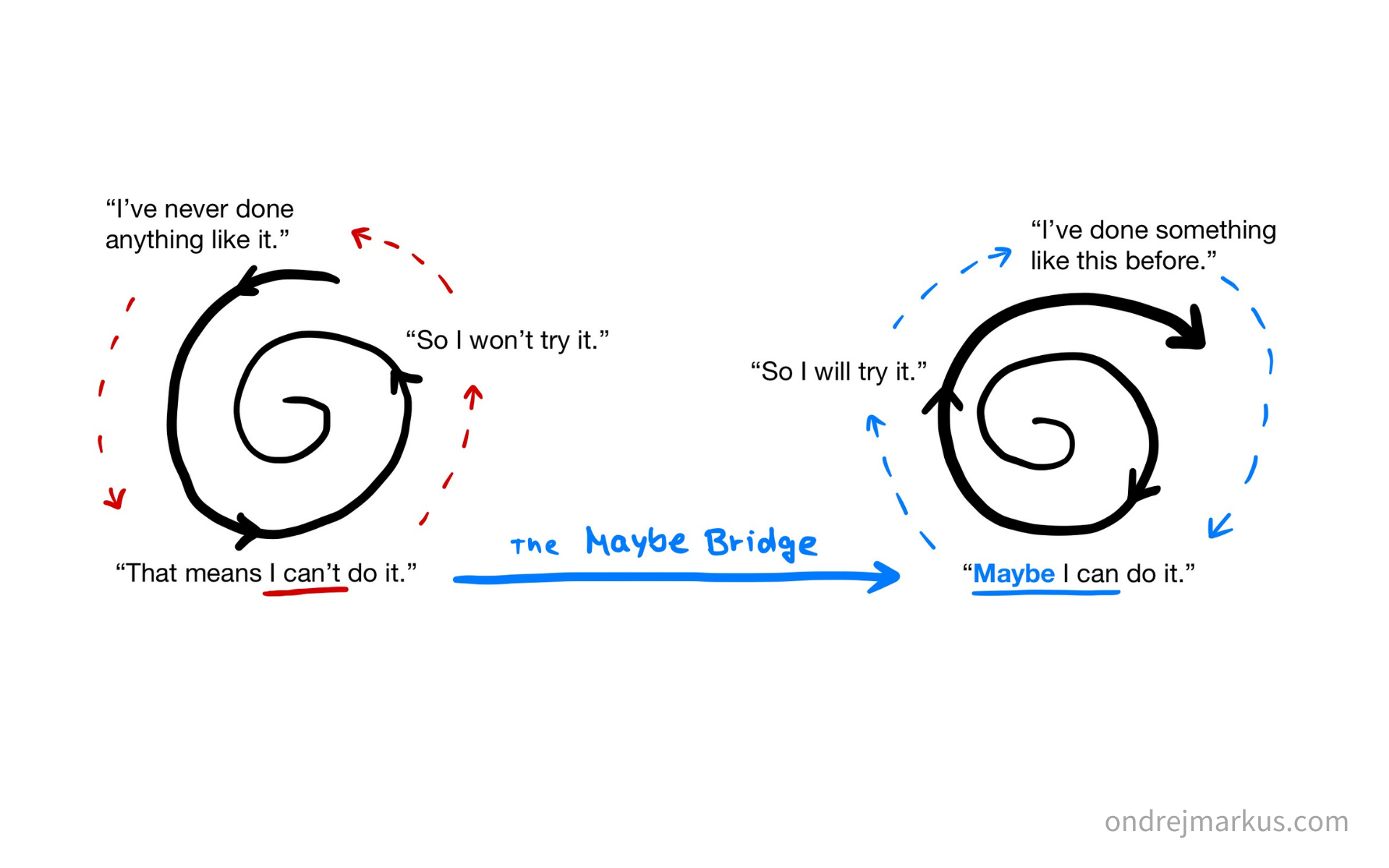

The test comes, when we made our plans and are ready for action. It’s too easy to persuade ourselves to keep planning and researching because we don’t feel ready. But we might never feel ready. We might think we can’t do it because there is no evidence of us ever accomplishing anything like it, so why bother trying? At the same time, there won’t ever be any evidence if we don’t act first. The only way to get out of this depressive circle is to leap out of the downward spiral and onto the upward spiral. We have to walk over the Maybe bridge.

The Maybe bridge is a mindset, in which you can create proof of your abilities for yourself – evidence of your competence – before you feel ready. And yes, from time to time, you won’t meet your expectations of success, but it doesn’t matter. Once you discover the Maybe bridge and learn to use it, you can do anything.

We’ll apply our newly gain bias for action right away.

Use worksheet: Step 10: Action plan

Questions

Start by listing questions you need to answer to move forward in the first phase of the experiment.

What do you need to answer to test your new work-life?

Sources

Secondly, think about sources you can research (websites, books), or talk to (people, who live the work-life we want to have).

Where can you find answers to your questions?

Actions

Thirdly, make an action plan of specific tasks you know you need to do to start phase 1.

What are you going to do?

After you finish, set up a 5-minute timer, and start right now. Just for 5 minutes. Do one thing.

Start before you feel ready

Your priority now is to prove to yourself you can begin your walk over the Maybe bridge and reach the work-life you want. Start now.

Big thanks to Linette and Dan for reading long drafts of this.

If you have any thoughts about the guide, want to share your insights, or tell me which picture you liked the most, write me an email.

Summary

- What do you want? If you can answer it specifically and genuinely, everything else follows naturally.

- Focus more on activities than outcomes

- Joy is the best fuel for learning

- Work to live, don’t live to work

- Don’t commit, experiment first. Keep your options open.

- There is no one perfect work you were born to do. There is more than one work-life that can fulfill your longings.

- Don’t quit your current job until you test your assumptions. We are horrible at predictions.

- Embrace bias for action to create your own evidence of competence. Act before you feel ready.

Sources

Where to go next:

Wait But Why

Tim Urban’s blog post is what inspired me to dig deeper into this topic and write about it. The Day 1 chapter is heavily based on his article. If you are looking for a place to continue, I can’t recommend this enough. Also, his illustrations are hilarious.

- How to Pick a Career (That Actually Fits You) (Start here.)

- The Cook and the Chef: Musk’s Secret Sauce (Also a good one if you like reading about Elon Musk.)

Seth’s blog

Seth Godin publishes blog posts every day. His thinking on how to approach work-life and how it fits into our culture resonates with me strongly. Here are some of his best blog posts related to work.

- Two kinds of 9 to 5 job

- Your job vs. your project

- Ignore sunk costs

- Hard work vs. Long work

- Everyone’s model of work is a job

School of Life

Collection of thoughts by the School of Life. Their gentle view on work and search for meaning in life encourages me to keep learning.

- Career therapy (article)

- How to Find Fulfilling Work (video)

80 000 hours

If you want your work to be useful you shouldn’t miss 80k hours. They offer science-backed guidance about what careers you should pick if you want to have the biggest positive impact possible.

- Career guide (articles)

Other sources

- Paul Graham - How to Do What You Love (essay)

- Stanford d.school - Designing the rest of your life (TED talk)

- Ichiro Kishimi, Fumitake Koga - The Courage to Be Disliked (book)

- Alan Watts – What Would You Do If Money Were No Object? Alan Watts on the Life of Purpose (video)