Ondrej Markus

Entrepreneur in ed-tech, building the future of education as a founder and CEO at Playful.

I write about the future of education, designing learning games, and running a startup.

I'm a generalist, introvert, gamer, and optimizing to be useful.

Test your idea in 280 characters

When I was building my first business 10 years ago, I thought I had a solid product idea. But I was afraid someone might steal it from me, so I worked in isolation for 6 months until I launched it. At that point, I was out of money, and I had to succeed at once to survive.

However, people didn’t want my product. Something was wrong but I couldn’t tell what it is. And that was the end of my business.

How is it possible that after more than 180 days of effort I made something people didn’t want?

Share your ideas earlier

My business failed because I kept it mostly a secret. I didn’t test my ideas with others until it was too late to change anything. I guessed what people wanted and I was wrong.

What I should have done instead is talk to people early and often about my idea. I would get helpful feedback on how much my product should cost, how it should look, and decide whether it’s an idea worth pursuing in the first place.

Talk to people early enough

The good news is that you don’t need refined skills and complex software to do this. All you need to start testing your ideas is words.

How to make Tweet prototypes

The simplest kind of prototype I like to use is what I call a Tweet prototype.

Tweet prototypes are text-only prototypes that are just 280 characters long. (Yes, like a tweet. 👏) And they’re perfect for early testing because they’re quick and easy to make.

Their purpose is to briefly explain your idea to someone else and get their reaction:

- Do they understand your idea?

- Do they want what you’re making?

The first part – being understood – is crucial in improving your idea because people cannot want something they do not understand.

That’s why Tweet prototypes are intentionally short and specific. They describe in 3 or 4 brief sentences What you’re making, Why is it useful, and How it works. That’s all.

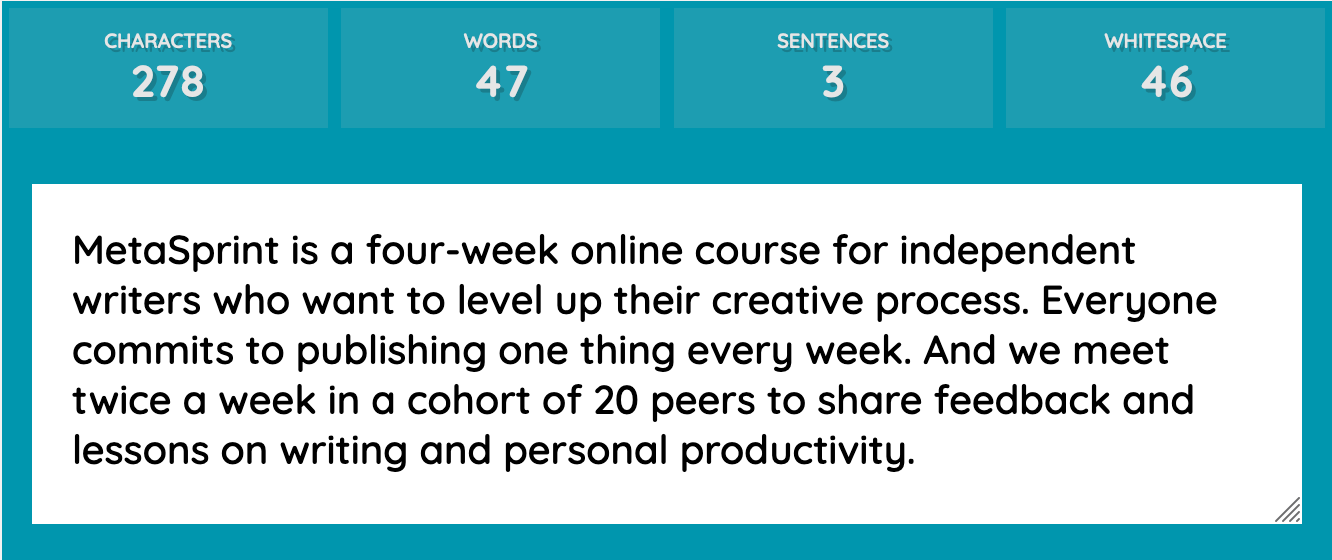

Let’s look at an example from a writing course I’m working on:

Tweet prototype example

Like most prototypes, this isn’t perfect. But what matters is that it includes the important parts of What, Why, and How:

- WHAT: The first sentence tells it’s a course for writers and it has to do with improving their creative process. The last part overlaps into the Why, but that’s okay as long as they’re all there.

- WHY: Here it hints at the ultimate goal – publishing work consistently.

- HOW: Lastly, there is a bit about what to expect will happen: the frequency of meetings (twice a week), how many people are there (20), and what are we going to talk about (writing and productivity).

Of course, anyone who reads this will have follow-up questions. That’s okay. The point here isn’t to explain everything. Tweet prototypes are a conversation starter.

Go talk to people

After writing this prototype, I would send it to one or two friends who might be interested. I’d hit them with an email saying something like: “Hey, I have this idea for a course. What do you think?”.

Most likely, they wouldn’t understand something I thought was obvious (but really wasn’t), so I would ask them follow-up questions.

- If you had to guess what this is, what would you think?

- What is confusing for you here?

- Who do you think this is for?

- What information is missing here?

This would help me make the prototype easier to understand. Then I’d repeat this process and add more people as I continued developing the idea.

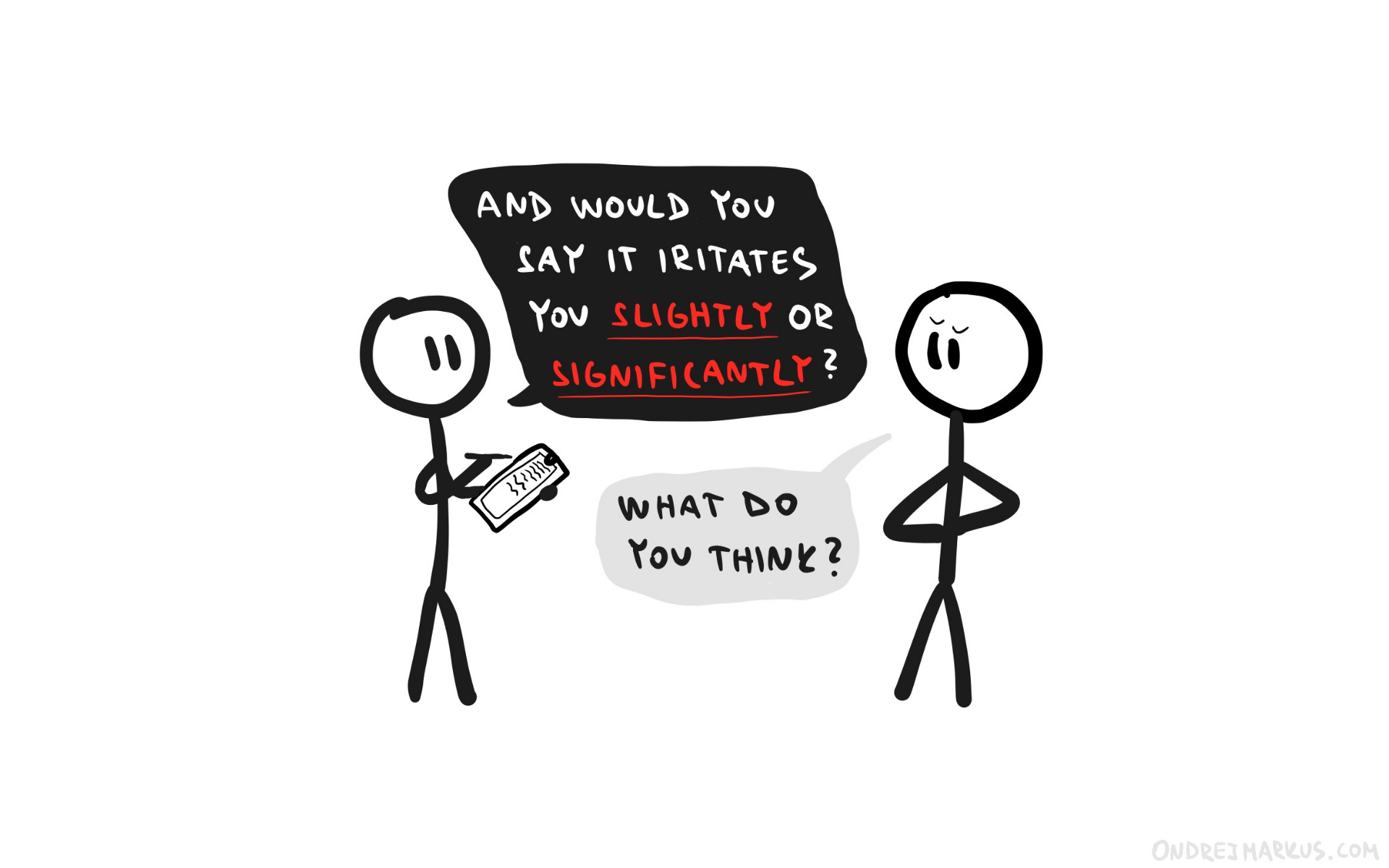

Ask good questions (not like this)

Just by doing this, you can very quickly move from an idea people don’t understand to something they actually want. And the best thing is that all this can happen in one afternoon because working with words is fast.

Create your first prototype right now

Do you have an idea to test?

- Open this online text editor

- Set a timer for 5 minutes

- Write 280 characters of What is your idea, Why is it useful, and How it works

- Send it to one friend who might like it.